|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 10 - 12 Jan 2018 - Main.EbenMoglen

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

No Suffrage, Little Attention; Nonetheless, Some Prosperity | | | Bush Goes West | |

<

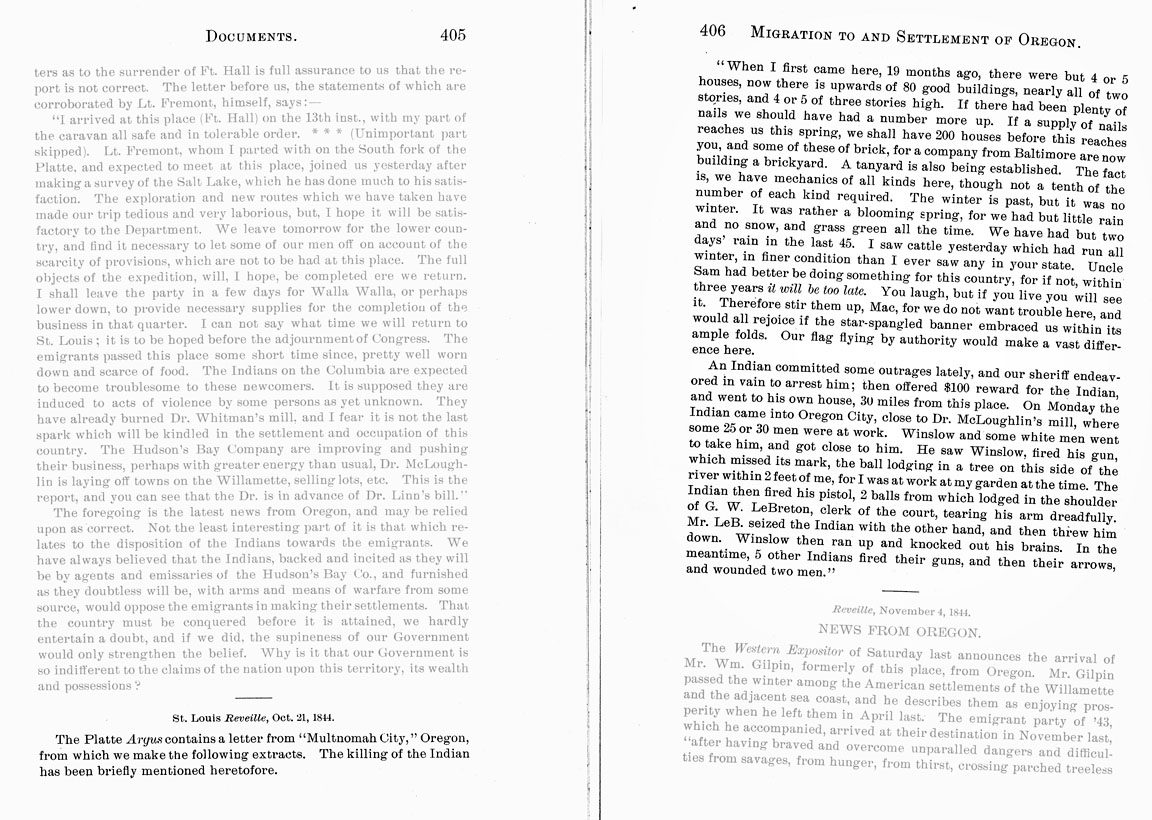

< | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant in whose manor they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After a decade of trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons, and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families.

Notes

:

| >

> | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India,

No, not even the one

source you are copying from says this. According to the

document at HistoryLink.org, "His father, Matthew Bush, of

African descent, was said to be a sailor from the British West

Indies." That's not an African from India, for sure. There are, according to the HistoryLink tertiary source, a number of secondaries to have consulted. If you did, for example for the inheritance story you tell below, which is not in any source you cite, you certainly should have cited it.

and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant in whose manor they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains.

Believed by whom?

What sources on that subject were consulted? Where does the Battle

of New Orleans story come from?

After a decade of trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons, and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | | | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, the present White community enforced Black Exclusion. Bush's party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound, at Tumwater (presently Olympia), between the Black and Deschutes Rivers. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill that served White settlers and Indians from St!sch!a's village.

Notes

:

:

| |

>

> |

That doesn't look like a genuine citation: An entire book for one fact, with no page reference. Did you see the source?

| | |

In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000 (according to the federal census). Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants.

Notes

:

:

:

| | | Washington’s White-Indian population swings can explain the legislature’s silence on Black affairs. By 1860, 40 Black people lived and worked among small encampments and budding cities. Most were single men employed by the Army or Navy. Whites numbered 11,318. Indians’ populations may have exceeded 25,000. By 1870, 207 Black and mixed-race Black people lived in Washington Territory. Whites numbered 22,195. Indians numbered 14,796. As remarked in Esther Mumford's Seattle's Black Victorians, the Black community in settler-era Washington was relatively meek, so they did not garner much legislative or political attention – nevertheless, a step up from the abject racism that many Black settlers fled.

Notes

:

:

:

| |

<

< | Throughout this period of Washington’s history, from settlement to territory, the legislature sought to engender White rights in predominantly Indian-held territory. The relatively few Black people did not enjoy civil rights, particularly suffrage; however, the land was rich and Washington’s policies did not strip Blacks of the right to till the soil and trade wares. Despite persistent difficulties, some natural and some social, Black people could prosper in Washington. As a result, Washington was a superior territory to Oregon for Black livelihoods. | >

> |

Same problem. An entire book is cited for one editorialization, without a page reference. Is the reader supposed to procure the book and look in the index for "meekness"? Did you see the source? On what basis should we conclude that there wasn't any "abject racism" facing a population of scarcely 200 Negroes among roughly 40,000 other people?

Throughout this period of Washington’s history, from settlement to territory, the legislature sought to engender White rights in predominantly Indian-held territory. The relatively few Black people did not enjoy civil rights, particularly suffrage;

"Particularly" or only? What other evidence is there concerning "civil rights"?

however, the land was rich and Washington’s policies did not strip Blacks of the right to till the soil and trade wares. Despite persistent difficulties, some natural and some social, Black people could prosper in Washington. As a result, Washington was a superior territory to Oregon for Black livelihoods.

I'm not sure what

this all adds up to. You have apparently verified that there were

no Negro voters in Washington before the 15th Amendment, though

you don't give any parallel information from the period

thereafter. Census data and electoral information should be

available for 1880 and 1890 if it is available for the earlier

period. In any event, this fact in itself doesn't give us

anything to interpret or to understand beyond the immediate negative.

The anecdotes about George Washington Bush and his offspring don't

seem to take us far beyond the run of the local history mill.

(You refer to his children as "mixed-race," and to him as "Black,"

but there doesn't seem to be any reason for the distinction. His

own father is said in the only source I could consult to be "of

African descent," and his own mother was white. Under "one drop"

doctrine such as would have applied in Louisiana or Mississippi

[were those the rules of the Oregon Territory Negro exclusion

law?] all of them were colored; under your vocabulary, they all

appear to have been of "mixed race" to an unknown degree.) How

does anything we learn about George W. Bush affect anything we are

supposed to conclude from the presence of a few dozen households

of "Black" or "Negro" people who didn't vote in Washington before

and immediately after territorial organization? | | | | |

>

> | | | |

-- JohnOMeara - 02 Nov 2016 - 04 Dec 2017 |

|

|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 9 - 12 Jan 2018 - Main.JohnOMeara

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

No Suffrage, Little Attention; Nonetheless, Some Prosperity | | | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, the present White community enforced Black Exclusion. Bush's party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound, at Tumwater (presently Olympia), between the Black and Deschutes Rivers. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill that served White settlers and Indians from St!sch!a's village. | |

<

< |

Notes

:

| >

> |

| | | In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000 (according to the federal census). Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants. |

|

|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 8 - 12 Jan 2018 - Main.JohnOMeara

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

No Suffrage, Little Attention; Nonetheless, Some Prosperity

| |

<

< | A wealthy half-Black war veteran and frontiersman named George Washington Bush altered the course of history in the Pacific Northwest. Bush was among the first Oregon Trail settlers in present-day Washington. Racism persisted north of the Columbia River, yet policies in Washington Territory were more conducive to Black prosperity than contemporaneous laws in Oregon Territory. Between 1844–1870, small Black enclaves established livelihoods in hardscrabble Washington Territory. The Bush family became prominent. In comparison, Oregon Territory enforced two “Black Exclusion” laws, and its constitution codified abject White supremacy. | >

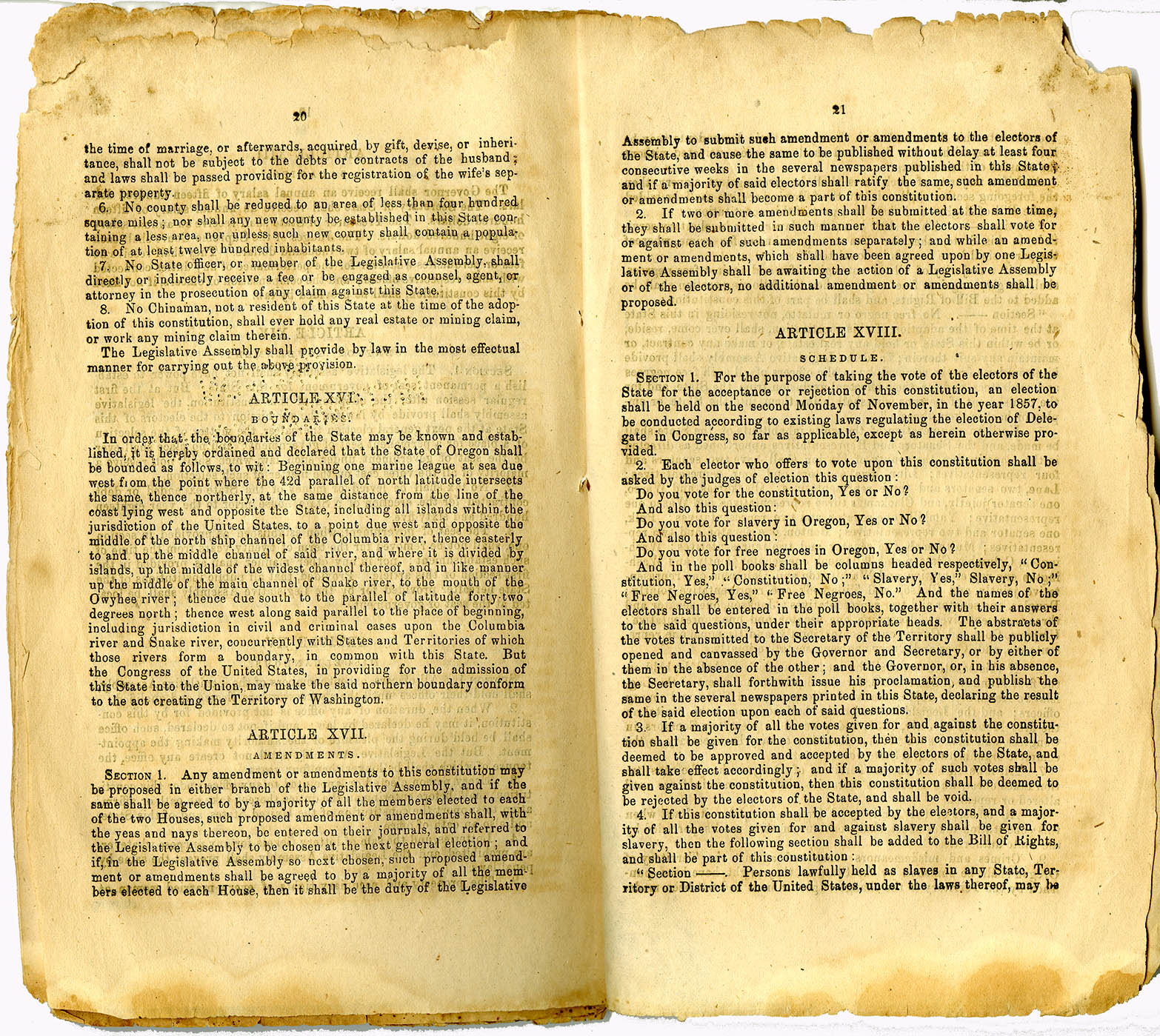

> | A wealthy half-Black war veteran and frontiersman named George Washington Bush altered the course of history in the Pacific Northwest. Bush was among the first Oregon Trail settlers in present-day Washington. Racism persisted north of the Columbia River, yet policies in Washington Territory were more conducive to Black prosperity than contemporaneous laws in Oregon Territory. Between 1844–1870, small Black enclaves established livelihoods in hardscrabble Washington Territory. The Bush family became prominent. In comparison, Oregon Territory enforced two “Black Exclusion” laws, and its constitution codified abject White supremacy.

Notes

:

:

| | | Given that Washington Territory’s legislature demonstrated greater interracial tolerance compared to its southern neighbors, did any Black men vote in Washington? | |

<

< | No.

Notes

:

| >

> | No.

Notes

:

| | | | |

<

< | My research concludes that no Black man appeared on a Washington Territory voter roll until after states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment. | >

> | My research concludes that no Black man appeared on a Washington Territory voter roll before states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. | | | | |

<

< | Nonetheless, by 1870, over two hundred free Blacks and “mulattoes,” mostly single men, acquired land or earned a living in Washington Territory. Before his death in 1863, Bush became prominent for business, charity and civics. His son, William, served in the state’s first legislature in 1889, and William introduced a successful civil rights bill in 1890. Bush was instrumental in early Washington's growth—but he never voted.

Notes

:

| >

> | Nonetheless, by 1870, over two hundred free Blacks and “mulattoes,” mostly single men, acquired land or earned a living in Washington Territory. Before his death in 1863, Bush became prominent for business, charity and civics. His son, William, served in the state’s first legislature in 1889, and William introduced a successful civil rights bill in 1890. Bush was instrumental in early Washington's growth—but he never voted.

Notes

:

:

:

:

:

:

| | |

Background: Hostility Toward Blacks in Oregon Country | |

<

< | A small settler population convened the Oregon Provisional Government in 1843. Skirmishes among settlers and Indians preoccupied the nascent government. After the deadly Cockstock Incident, arising from a dispute between a Black settler and a servant Indian, Oregon enacted the first of two Black Exclusion laws. The law forbade Blacks, free or slave, from entering or residing in Oregon Country, and it released bonded Black servants and subsequently required their removal from the territory. Black settlers were to be publicly lashed every six months until and unless their departure from the territory. Oregon’s legislature repealed the statute in 1846 before a public whipping occurred. Instead of the lash, Whites banished Blacks at risk of being auctioned into slavery if they stayed. | >

> | A small settler population convened the Oregon Provisional Government in 1843. Skirmishes among settlers and Indians preoccupied the nascent government. After the deadly Cockstock Incident, arising from a dispute between a Black settler and a servant Indian, Oregon enacted the first of two Black Exclusion laws.

The law forbade Blacks, free or slave, from entering or residing in Oregon Country, and it released bonded Black servants and subsequently required their removal from the territory. Black settlers were to be publicly lashed every six months until and unless their departure from the territory. Oregon’s legislature repealed the statute in 1846 before a public whipping occurred. Instead of the lash, Whites banished Blacks at risk of being auctioned into slavery if they stayed.

Notes

:

:

:

| | | | |

<

< | In 1849, the Oregon Territorial Government enacted a second Black Exclusion law. This effectuated the expulsion of (only) one Black man, Jacob Vanderpool. The Oregon Territorial Government repealed this law in 1853 but imposed similarly exclusionary laws it in its 1857 constitution, effective upon statehood in 1859. The constitution forbade Black residence, real estate ownership, contracting, suffrage and use of the state’s judicial system. | >

> | In 1849, the Oregon Territorial Government enacted a second Black Exclusion law. This effectuated the expulsion of (only) one Black man, Jacob Vanderpool. The Oregon Territorial Government repealed this law in 1853 but imposed similarly exclusionary laws it in its 1857 constitution, effective upon statehood in 1859. The constitution forbade Black residence, real estate ownership, contracting, suffrage and use of the state’s judicial system. These laws did not include enforcement mechanisms or grant jurisdiction to counties to police the exclusion laws, which is why a relatively small (and beleaguered) Black population tenuously existed in Oregon between 1850 — 1860. | | |

Bush Goes West | |

<

< | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant in whose manor they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After a decade of trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons, and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | >

> | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant in whose manor they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After a decade of trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons, and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | | | | |

<

< | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, the present White community enforced Black Exclusion. Bush's party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound, at Tumwater (presently Olympia), between the Black and Deschutes Rivers. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill that served White settlers and Indians from St!sch!a's village. | >

> | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, the present White community enforced Black Exclusion. Bush's party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound, at Tumwater (presently Olympia), between the Black and Deschutes Rivers. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill that served White settlers and Indians from St!sch!a's village. | | | | |

<

< | In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000. Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants. | >

> |

| | | | |

>

> | In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000 (according to the federal census). Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants. | | | | |

<

< | Founding Washington Territory | | | | |

<

< | Settlers in Clark and Lewis Counties began organizing a provisional independent government in 1851. They drafted a petition to Congress to form a new Territory at the Monticello Convention, November 25–26, 1852. Upon enactment of the Organic Act, Washington Territory split from Oregon on March 2, 1853. | >

> | Founding Washington Territory, But Not Necessarily Voting In It | | | | |

>

> | Settlers in Clark and Lewis Counties began organizing a provisional independent government in 1851. They drafted a petition to Congress to form a new Territory at the Monticello Convention, November 25–26, 1852. Upon enactment of the Organic Act, Washington Territory split from Oregon on March 2, 1853.

Notes

:

| | | | |

<

< | The Organic Act did not adopt Black Exclusion policies. Indeed, the act does not mention Black people. Under the Organic Act, White and mixed-race White-Indian male residents had exclusive voting eligibility to elect the first assembly. Voter eligibility in subsequent elections was to be determined by this assembly. | >

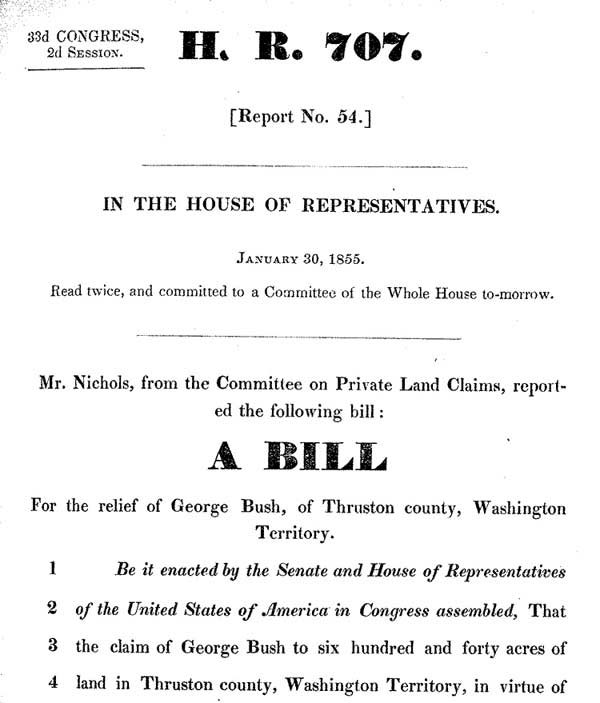

> | The Organic Act did not adopt Black Exclusion policies. Indeed, the act does not mention Black people. Under the Organic Act, White and mixed-race White-Indian male residents had exclusive voting eligibility to elect the first assembly. Voter eligibility in subsequent elections was to be determined by this assembly. The initial election elevated 29 men to the Territorial Assembly. One of the Councilmen, Michael T. Simmons, was in Bush’s 1844 Oregon Trail party. Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens presided. The first assembly session concluded February 27, 1854.

Notes

:

:

:

| | | | |

<

< | The initial election elevated 29 men to the Territorial Assembly. One of the Councilmen, Michael T. Simmons, was in Bush’s 1844 Oregon Trail party. Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens presided. The first assembly session concluded February 27, 1854. Legislators declined to give the few Black men voting rights. Consequently, I found no record that Black people attempted to register to vote between 1854—1870. In comparison, many mixed-race White-Indian men participated in elections. | >

> | Legislators declined to give the few Black men voting rights. Consequently, I found no record that Black people attempted to register to vote between 1854—1870. In comparison, many mixed-race White-Indian men participated in elections. | | |

A Small Population Aroused Little Attention | |

<

< | Black people who came West lived under less pointed racist public policies in Washington than in Oregon. For instance, in 1855, Washington’s Assembly unanimously voted to petition Congress to confirm Bush’s freehold title on Bush Prairie; Congress granted it. For the most part, Washington Territory’s laws were silent on Black affairs. However, the same session 1855 session that supported Bush’s property claim enacted an anti-miscegenation law. | >

> | Black people who came West lived under less pointed racist public policies in Washington than in Oregon. For instance, in 1855, Washington’s Assembly unanimously voted to petition Congress to confirm Bush’s freehold title on Bush Prairie; Congress granted it.

Notes

:

:

| | | | |

<

< | Washington’s White-Indian population swings can explain the legislature’s silence on Black affairs. By 1860, 40 Black people lived and worked among small encampments and budding cities. Most were single men employed by the Army or Navy. Whites numbered 11,318. Indians’ populations may have exceeded 25,000. By 1870, 207 Black and mixed-race Black people lived in Washington Territory. Whites numbered 22,195. Indians numbered 14,796. Blacks were relatively meek, so they did not garner attention. | >

> |

| | | | |

<

< | Throughout this period of Washington’s history, from settlement to territoryhood, the legislature sought to engender White rights in predominantly Indian-held territory. The relatively few Black people did not enjoy civil rights, particularly suffrage; however, the land was rich and Washington’s policies did not strip Blacks of the right to till the soil and trade wares. As a result, Washington was a superior territory to Oregon for Black livelihoods. | >

> | For the most part, Washington Territory’s laws were silent on Black affairs. However, the same 1855 Territorial Assembly session that supported Bush’s property claim enacted an anti-miscegenation law.

Washington’s White-Indian population swings can explain the legislature’s silence on Black affairs. By 1860, 40 Black people lived and worked among small encampments and budding cities. Most were single men employed by the Army or Navy. Whites numbered 11,318. Indians’ populations may have exceeded 25,000. By 1870, 207 Black and mixed-race Black people lived in Washington Territory. Whites numbered 22,195. Indians numbered 14,796. As remarked in Esther Mumford's Seattle's Black Victorians, the Black community in settler-era Washington was relatively meek, so they did not garner much legislative or political attention – nevertheless, a step up from the abject racism that many Black settlers fled.

Throughout this period of Washington’s history, from settlement to territory, the legislature sought to engender White rights in predominantly Indian-held territory. The relatively few Black people did not enjoy civil rights, particularly suffrage; however, the land was rich and Washington’s policies did not strip Blacks of the right to till the soil and trade wares. Despite persistent difficulties, some natural and some social, Black people could prosper in Washington. As a result, Washington was a superior territory to Oregon for Black livelihoods.

Notes

:

| | | | | |

| |

>

> |

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="bc950d6c-0d19-49bb-8766-3ec9608c8b2d.pdf" attr="" comment="1850 U.S. Federal Census - Lewis County, Ore. Terr." date="1515764740" name="bc950d6c-0d19-49bb-8766-3ec9608c8b2d.pdf" path="bc950d6c-0d19-49bb-8766-3ec9608c8b2d.pdf" size="4245392" stream="bc950d6c-0d19-49bb-8766-3ec9608c8b2d.pdf" user="Main.JohnOMeara" version="1" |

|---|

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="03-Organic.pdf" attr="" comment="The Organic Act of Washington Territory (1853)" date="1515768685" name="03-Organic.pdf" path="03-Organic.pdf" size="133427" stream="03-Organic.pdf" user="Main.JohnOMeara" version="1" |

|---|

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="Screen_Shot_2018-01-12_at_9.49.49_AM.png" attr="" comment="Section 5 of the Organic Act, %22Qualifications of voters%22" date="1515768726" name="Screen_Shot_2018-01-12_at_9.49.49_AM.png" path="Screen Shot 2018-01-12 at 9.49.49 AM.png" size="322495" stream="Screen Shot 2018-01-12 at 9.49.49 AM.png" user="Main.JohnOMeara" version="1" |

|---|

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="Screen_Shot_2018-01-12_at_10.04.04_AM.png" attr="" comment="Anti-Miscegenation Law, WA Terr. Laws (1855)" date="1515769545" name="Screen_Shot_2018-01-12_at_10.04.04_AM.png" path="Screen Shot 2018-01-12 at 10.04.04 AM.png" size="273249" stream="Screen Shot 2018-01-12 at 10.04.04 AM.png" user="Main.JohnOMeara" version="1" |

|---|

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="Screen_Shot_2018-01-12_at_10.10.30_AM.png" attr="" comment="Census records, 1870" date="1515770593" name="Screen_Shot_2018-01-12_at_10.10.30_AM.png" path="Screen Shot 2018-01-12 at 10.10.30 AM.png" size="702365" stream="Screen Shot 2018-01-12 at 10.10.30 AM.png" user="Main.JohnOMeara" version="1" |

|---|

|

|

|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 7 - 11 Jan 2018 - Main.JohnOMeara

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

No Suffrage, Little Attention; Nonetheless, Some Prosperity | |

>

> |

| | | A wealthy half-Black war veteran and frontiersman named George Washington Bush altered the course of history in the Pacific Northwest. Bush was among the first Oregon Trail settlers in present-day Washington. Racism persisted north of the Columbia River, yet policies in Washington Territory were more conducive to Black prosperity than contemporaneous laws in Oregon Territory. Between 1844–1870, small Black enclaves established livelihoods in hardscrabble Washington Territory. The Bush family became prominent. In comparison, Oregon Territory enforced two “Black Exclusion” laws, and its constitution codified abject White supremacy.

Given that Washington Territory’s legislature demonstrated greater interracial tolerance compared to its southern neighbors, did any Black men vote in Washington? |

|

|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 6 - 11 Jan 2018 - Main.JohnOMeara

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

No Suffrage, Little Attention; Nonetheless, Some Prosperity | |

<

< | A wealthy half-Black war veteran and frontiersman named George Washington Bush altered the course of history in the Pacific Northwest. George Bush was among the first Oregon Trail settlers in present-day Washington. Racism persisted north of the Columbia River, yet policies in Washington Territory were more conducive to Black prosperity than contemporaneous laws in Oregon Territory. Between 1844–1870, small Black enclaves established livelihoods in hardscrabble Washington Territory. The Bush family became prominent. In comparison, Oregon Territory enforced two “Black Exclusion” laws, and its constitution codified abject White supremacy. | >

> | A wealthy half-Black war veteran and frontiersman named George Washington Bush altered the course of history in the Pacific Northwest. Bush was among the first Oregon Trail settlers in present-day Washington. Racism persisted north of the Columbia River, yet policies in Washington Territory were more conducive to Black prosperity than contemporaneous laws in Oregon Territory. Between 1844–1870, small Black enclaves established livelihoods in hardscrabble Washington Territory. The Bush family became prominent. In comparison, Oregon Territory enforced two “Black Exclusion” laws, and its constitution codified abject White supremacy. | | | Given that Washington Territory’s legislature demonstrated greater interracial tolerance compared to its southern neighbors, did any Black men vote in Washington? | |

<

< | No. | >

> | No. | | | My research concludes that no Black man appeared on a Washington Territory voter roll until after states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment. | |

<

< | Nonetheless, by 1870, over two hundred free Blacks and “mulattoes,” mostly single men, acquired land or earned a living in Washington Territory. Before his death in 1863, Bush became prominent for business, charity and civics. His son, William, served in the state’s first legislature in 1889, and William introduced a successful civil rights bill in 1890. Bush was instrumental in early Washington's growth—but he never voted. | >

> | Nonetheless, by 1870, over two hundred free Blacks and “mulattoes,” mostly single men, acquired land or earned a living in Washington Territory. Before his death in 1863, Bush became prominent for business, charity and civics. His son, William, served in the state’s first legislature in 1889, and William introduced a successful civil rights bill in 1890. Bush was instrumental in early Washington's growth—but he never voted. | | |

Background: Hostility Toward Blacks in Oregon Country | |

<

< | A small settler population convened the Oregon Provisional Government in 1843. Skirmishes among settlers and Indians preoccupied the nascent government. After the deadly Cockstock Incident, arising from a dispute between a Black settler and a servant Indian, Oregon enacted the first of two Black Exclusion laws. The law forbade Blacks, free or slave, from entering or residing in Oregon Country, and it released bonded Black servants and subsequently required their removal from the territory. Black settlers were to be publicly lashed every six months until and unless their departure from the territory. Oregon’s legislature repealed the statute in 1846 before a public whipping occurred. Instead of the lash, Whites banished Blacks at risk of being auctioned into slavery if they stayed.*1.? | >

> | A small settler population convened the Oregon Provisional Government in 1843. Skirmishes among settlers and Indians preoccupied the nascent government. After the deadly Cockstock Incident, arising from a dispute between a Black settler and a servant Indian, Oregon enacted the first of two Black Exclusion laws. The law forbade Blacks, free or slave, from entering or residing in Oregon Country, and it released bonded Black servants and subsequently required their removal from the territory. Black settlers were to be publicly lashed every six months until and unless their departure from the territory. Oregon’s legislature repealed the statute in 1846 before a public whipping occurred. Instead of the lash, Whites banished Blacks at risk of being auctioned into slavery if they stayed. | | | In 1849, the Oregon Territorial Government enacted a second Black Exclusion law. This effectuated the expulsion of (only) one Black man, Jacob Vanderpool. The Oregon Territorial Government repealed this law in 1853 but imposed similarly exclusionary laws it in its 1857 constitution, effective upon statehood in 1859. The constitution forbade Black residence, real estate ownership, contracting, suffrage and use of the state’s judicial system.

Bush Goes West | |

<

< | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant in whose manor they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After a decade of trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons,*2.? and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | >

> | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant in whose manor they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After a decade of trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons, and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | | | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, the present White community enforced Black Exclusion. Bush's party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound, at Tumwater (presently Olympia), between the Black and Deschutes Rivers. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill that served White settlers and Indians from St!sch!a's village. | |

<

< | In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000. Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants.*3.? | >

> | In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000. Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants. | | |

Founding Washington Territory

Settlers in Clark and Lewis Counties began organizing a provisional independent government in 1851. They drafted a petition to Congress to form a new Territory at the Monticello Convention, November 25–26, 1852. Upon enactment of the Organic Act, Washington Territory split from Oregon on March 2, 1853. | |

<

< | [INSERT: excerpt of Monticello Convention] | | | The Organic Act did not adopt Black Exclusion policies. Indeed, the act does not mention Black people. Under the Organic Act, White and mixed-race White-Indian male residents had exclusive voting eligibility to elect the first assembly. Voter eligibility in subsequent elections was to be determined by this assembly. | |

<

< | **Screenshot of Sec. 4** | | | The initial election elevated 29 men to the Territorial Assembly. One of the Councilmen, Michael T. Simmons, was in Bush’s 1844 Oregon Trail party. Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens presided. The first assembly session concluded February 27, 1854. Legislators declined to give the few Black men voting rights. Consequently, I found no record that Black people attempted to register to vote between 1854—1870. In comparison, many mixed-race White-Indian men participated in elections. | |

<

< | INSERT: excerpt of 1854 laws, § 1 | | | A Small Population Aroused Little Attention | | | | |

<

< | Footnotes

1.) In 1846, President Polk signed a bilateral treaty, the Oregon Treaty, demarcating borders between British Columbia and American territory. Oregon Territory was established in 1848, and its borders changed twice thereafter. Bush’s party may have been able to develop settlements north of the Columbia River, in disputed territory, because Bush had contacts in Fort Vancouver from his time with Hudson’s Bay Company fur traders.

2.) The children were aged eleven, eight, five and two during the transcontinental trip. According to the 1850 federal census, Isabella Bush gave birth to Louis, her fifth son, in 1846. Louis is believed to be the first “mulatto” Black child born west of the Rockies.

3.)The 1850 federal Census for Clark County includes four “Dark Hawaiian” men who were initially marked as Black residents.

| | | -- JohnOMeara - 02 Nov 2016 - 04 Dec 2017 |

|

|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 5 - 05 Jan 2018 - Main.JohnOMeara

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

No Suffrage, Little Attention; Nonetheless, Some Prosperity

A wealthy half-Black war veteran and frontiersman named George Washington Bush altered the course of history in the Pacific Northwest. George Bush was among the first Oregon Trail settlers in present-day Washington. Racism persisted north of the Columbia River, yet policies in Washington Territory were more conducive to Black prosperity than contemporaneous laws in Oregon Territory. Between 1844–1870, small Black enclaves established livelihoods in hardscrabble Washington Territory. The Bush family became prominent. In comparison, Oregon Territory enforced two “Black Exclusion” laws, and its constitution codified abject White supremacy. | |

<

< | Given that Washington Territory’s legislature demonstrated interracial tolerance compared to its southern neighbors, did any Black men vote in Washington? | >

> | Given that Washington Territory’s legislature demonstrated greater interracial tolerance compared to its southern neighbors, did any Black men vote in Washington? | | | No.

My research concludes that no Black man appeared on a Washington Territory voter roll until after states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment. | |

<

< | Nonetheless, by 1870, over two hundred free Blacks and “mulattoes,” mostly single men, acquired land or earned a living in Washington Territory. Before his death in 1863, Bush became prominent for business, charity and civics. His son, William, served in the state’s first legislature in 1889. Bush was instrumental in settling Washington—but he never voted. | >

> | Nonetheless, by 1870, over two hundred free Blacks and “mulattoes,” mostly single men, acquired land or earned a living in Washington Territory. Before his death in 1863, Bush became prominent for business, charity and civics. His son, William, served in the state’s first legislature in 1889, and William introduced a successful civil rights bill in 1890. Bush was instrumental in early Washington's growth—but he never voted. | | |

Background: Hostility Toward Blacks in Oregon Country | | | Bush Goes West | |

<

< | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant for whom they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons,*2.? and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | >

> | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant in whose manor they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After a decade of trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons,*2.? and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | | | | |

<

< | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, White farmers enforced Black Exclusion. The party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill. | >

> | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, the present White community enforced Black Exclusion. Bush's party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound, at Tumwater (presently Olympia), between the Black and Deschutes Rivers. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill that served White settlers and Indians from St!sch!a's village. | | | In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000. Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants.*3.? | | | [INSERT: excerpt of Monticello Convention] | |

<

< | The Organic Act did not adopt Black Exclusion policies. Indeed, the act does not mention Black people. Under the Organic Act, White and mixed-race White-Indian male residents had exclusive voting eligibility to elect an assembly. Voter eligibility in subsequent elections was to be determined by the assembly. | >

> | The Organic Act did not adopt Black Exclusion policies. Indeed, the act does not mention Black people. Under the Organic Act, White and mixed-race White-Indian male residents had exclusive voting eligibility to elect the first assembly. Voter eligibility in subsequent elections was to be determined by this assembly. | | | **Screenshot of Sec. 4** | |

<

< | The initial election elevated 29 men to the Territorial Assembly. One of the Councilmen, Michael T. Simmons, was in Bush’s 1844 Oregon Trail party. Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens presided. The first assembly session concluded February 27, 1854. Legislators declined to give the few Black men voting rights. Consequently, I found no record that Black people attempted to register to vote between 1854—1870. In comparison, many mixed-race White-Indian men participated in elections. | >

> | The initial election elevated 29 men to the Territorial Assembly. One of the Councilmen, Michael T. Simmons, was in Bush’s 1844 Oregon Trail party. Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens presided. The first assembly session concluded February 27, 1854. Legislators declined to give the few Black men voting rights. Consequently, I found no record that Black people attempted to register to vote between 1854—1870. In comparison, many mixed-race White-Indian men participated in elections. | | | INSERT: excerpt of 1854 laws, § 1 |

|

|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 4 - 04 Dec 2017 - Main.JohnOMeara

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

| |

<

< | --+ America Almost Guaranteed Universal Secular Education; But "Almost" Ain't Half of It. Too Bad. Dumb Luck. | >

> | No Suffrage, Little Attention; Nonetheless, Some Prosperity | | | | |

<

< | During President Grant's administration, American society's worst wounds had hardly scabbed. He attempted to enucleate and heighten America's promised freedoms, anyway. His administration struggled for every inch of proto-progressive regime-changing in terms of race, ethnicity, national origin and religion. There were some successes, many failures and much left misunderstood or forgotten. Seminal historical study has touched on or exhausted each of these topics. However, President Grant's near-miss with an landmark constitutional amendment is not well documented. | >

> | A wealthy half-Black war veteran and frontiersman named George Washington Bush altered the course of history in the Pacific Northwest. George Bush was among the first Oregon Trail settlers in present-day Washington. Racism persisted north of the Columbia River, yet policies in Washington Territory were more conducive to Black prosperity than contemporaneous laws in Oregon Territory. Between 1844–1870, small Black enclaves established livelihoods in hardscrabble Washington Territory. The Bush family became prominent. In comparison, Oregon Territory enforced two “Black Exclusion” laws, and its constitution codified abject White supremacy. | | | | |

<

< | In 1876, President Grant pushed hard for an amendment to the constitution that would have guaranteed basic secular education in America. Politically, it never stood a chance. The proposed amendment was certainly politically motivated and sui generis. President Grant personally pushed for the amendment in reaction to Reconstruction-era parochial nonsense in the South. President Grant and the proposed amendments' many Northern sponsors sent salvos into intransigent states, aimed at children's minds. I wish it had worked. | >

> | Given that Washington Territory’s legislature demonstrated interracial tolerance compared to its southern neighbors, did any Black men vote in Washington? | | | | |

<

< | According to historians, the agony of civil war remained the base chord of the national ethos throughout Grant's presidency. For his part, President Grant tried to humanize those de-humanized in the decades or centuries before he rose to prominence -- hyphenated Americans, of which Black America was a focal point, immigrants, and Jews became targets for political benefit. Facing the hornets nests in the South and in Congress, President Grant and AG Ackerman pursued a civil rights agenda, if only politically (i.e., symbolically). He also sought to quell the successes of the Klan and similar proto-terrorist groups. The difficulty of these tasks are well stated in James William Hurst's /Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth-Century United States/. Taking Hurst's word as canon, the Grant presidency is arguably typified by the desire to enable and support activity or policy that improved one's freedom -- personal freedoms of movement, gainful employment, social well being, to name a few. The backlash of this so-called movement in favor of novel freedoms was ultimately successful; Jim Crow persisted, for example. | >

> | No. | | | | |

<

< | However, Reconstruction-era order was tenuously held, and parochial society crept toward steam mobilization and the blossoming of technological modernity in cities. old America was moving westward and European immigrants | >

> | My research concludes that no Black man appeared on a Washington Territory voter roll until after states ratified the Fifteenth Amendment. | | | | |

<

< | Reconstruction Era Occasioned Communities to Resist Federal Influence, and Vice Versa | >

> | Nonetheless, by 1870, over two hundred free Blacks and “mulattoes,” mostly single men, acquired land or earned a living in Washington Territory. Before his death in 1863, Bush became prominent for business, charity and civics. His son, William, served in the state’s first legislature in 1889. Bush was instrumental in settling Washington—but he never voted. | | | | |

<

< | A confluence of exogenous pressures and deep seated insecurities during Reconstruction prompted Southerners and rural communities to foment resistance against normative, broad federal powers. | | | | |

<

< | The newly independent empire of the United States in its explosive,

expansionist phase was organized by law built around what Willard

Hurst called "the release of energy principle." In this section of

the course we consider that regime and its effects. | >

> | Background: Hostility Toward Blacks in Oregon Country | | | | |

>

> | A small settler population convened the Oregon Provisional Government in 1843. Skirmishes among settlers and Indians preoccupied the nascent government. After the deadly Cockstock Incident, arising from a dispute between a Black settler and a servant Indian, Oregon enacted the first of two Black Exclusion laws. The law forbade Blacks, free or slave, from entering or residing in Oregon Country, and it released bonded Black servants and subsequently required their removal from the territory. Black settlers were to be publicly lashed every six months until and unless their departure from the territory. Oregon’s legislature repealed the statute in 1846 before a public whipping occurred. Instead of the lash, Whites banished Blacks at risk of being auctioned into slavery if they stayed.*1.? | | | | |

<

< | Readings | >

> | In 1849, the Oregon Territorial Government enacted a second Black Exclusion law. This effectuated the expulsion of (only) one Black man, Jacob Vanderpool. The Oregon Territorial Government repealed this law in 1853 but imposed similarly exclusionary laws it in its 1857 constitution, effective upon statehood in 1859. The constitution forbade Black residence, real estate ownership, contracting, suffrage and use of the state’s judicial system. | | | | |

<

< | Access materials on the [Course Readings] page. | | | | |

>

> | Bush Goes West | | | | |

<

< | Assigned | >

> | George Bush’s African father, born in colonial India, and mother, Irish-American, inherited a fortune in 1787 from an heirless Philadelphian merchant for whom they served. Young Bush was educated, and he fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans at 21 years old. After the war, Bush fur-trapped in Oregon Country for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Bush is believed to be the first free Black man west of the Rocky Mountains. After trapping, Bush raised cattle in Illinois and Missouri. In 1844, Bush embarked from Missouri with his White wife, Isabella, four mixed-race sons,*2.? and several thousand dollars’ worth of ingot. Bush led a predominantly White party comprising several well-to-do families. | | | | |

>

> | Upon Bush’s arrival to the Willamette Valley, White farmers enforced Black Exclusion. The party relocated to the southern tip of Puget Sound. There, Bush established Bush Prairie, a successful farm, and financed a gristmill and a sawmill. | | | | |

<

< | From the Notebooks of Judge Thomas Rodney of the Mississippi Territory | >

> | In 1850, Bush owned real property in Lewis County worth $3,000. Among the county’s 558 residents, only seven heads of households had real property worth more. One other Black man, William Phillips, a sailor, lived in Lewis County. A Black man and woman, each a servant to a White Army officer, lived in Clark County. In 1850, nine Black people resided in Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River, of 1,201 total inhabitants.*3.? | | | | |

<

< | Suggested | | | | |

<

< | Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Wisconsin Press 1956) | >

> | Founding Washington Territory | | | | |

>

> | Settlers in Clark and Lewis Counties began organizing a provisional independent government in 1851. They drafted a petition to Congress to form a new Territory at the Monticello Convention, November 25–26, 1852. Upon enactment of the Organic Act, Washington Territory split from Oregon on March 2, 1853. | | | | |

<

< | Notes and Materials | >

> | [INSERT: excerpt of Monticello Convention] | | | | |

>

> | The Organic Act did not adopt Black Exclusion policies. Indeed, the act does not mention Black people. Under the Organic Act, White and mixed-race White-Indian male residents had exclusive voting eligibility to elect an assembly. Voter eligibility in subsequent elections was to be determined by the assembly. | | | | |

>

> | **Screenshot of Sec. 4** | | | | |

>

> | The initial election elevated 29 men to the Territorial Assembly. One of the Councilmen, Michael T. Simmons, was in Bush’s 1844 Oregon Trail party. Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens presided. The first assembly session concluded February 27, 1854. Legislators declined to give the few Black men voting rights. Consequently, I found no record that Black people attempted to register to vote between 1854—1870. In comparison, many mixed-race White-Indian men participated in elections. | | | | |

<

< | Projects | >

> | INSERT: excerpt of 1854 laws, § 1 | | | | |

>

> | A Small Population Aroused Little Attention | | | | |

>

> | Black people who came West lived under less pointed racist public policies in Washington than in Oregon. For instance, in 1855, Washington’s Assembly unanimously voted to petition Congress to confirm Bush’s freehold title on Bush Prairie; Congress granted it. For the most part, Washington Territory’s laws were silent on Black affairs. However, the same session 1855 session that supported Bush’s property claim enacted an anti-miscegenation law. | | | | |

>

> | Washington’s White-Indian population swings can explain the legislature’s silence on Black affairs. By 1860, 40 Black people lived and worked among small encampments and budding cities. Most were single men employed by the Army or Navy. Whites numbered 11,318. Indians’ populations may have exceeded 25,000. By 1870, 207 Black and mixed-race Black people lived in Washington Territory. Whites numbered 22,195. Indians numbered 14,796. Blacks were relatively meek, so they did not garner attention. | | | | |

>

> | Throughout this period of Washington’s history, from settlement to territoryhood, the legislature sought to engender White rights in predominantly Indian-held territory. The relatively few Black people did not enjoy civil rights, particularly suffrage; however, the land was rich and Washington’s policies did not strip Blacks of the right to till the soil and trade wares. As a result, Washington was a superior territory to Oregon for Black livelihoods. | | | | |

<

< | -- JohnOMeara - 02 Nov 2016 | >

> |

Footnotes

1.) In 1846, President Polk signed a bilateral treaty, the Oregon Treaty, demarcating borders between British Columbia and American territory. Oregon Territory was established in 1848, and its borders changed twice thereafter. Bush’s party may have been able to develop settlements north of the Columbia River, in disputed territory, because Bush had contacts in Fort Vancouver from his time with Hudson’s Bay Company fur traders.

2.) The children were aged eleven, eight, five and two during the transcontinental trip. According to the 1850 federal census, Isabella Bush gave birth to Louis, her fifth son, in 1846. Louis is believed to be the first “mulatto” Black child born west of the Rockies.

3.)The 1850 federal Census for Clark County includes four “Dark Hawaiian” men who were initially marked as Black residents.

-- JohnOMeara - 02 Nov 2016 - 04 Dec 2017 | | |

\ No newline at end of file |

|

|

JohnOMearaProject_DumbLuck 2 - 31 May 2017 - Main.JohnOMeara

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="WebPreferences" |

|---|

| |

>

> | --+ America Almost Guaranteed Universal Secular Education; But "Almost" Ain't Half of It. Too Bad. Dumb Luck.

During President Grant's administration, American society's worst wounds had hardly scabbed. He attempted to enucleate and heighten America's promised freedoms, anyway. His administration struggled for every inch of proto-progressive regime-changing in terms of race, ethnicity, national origin and religion. There were some successes, many failures and much left misunderstood or forgotten. Seminal historical study has touched on or exhausted each of these topics. However, President Grant's near-miss with an landmark constitutional amendment is not well documented.

In 1876, President Grant pushed hard for an amendment to the constitution that would have guaranteed basic secular education in America. Politically, it never stood a chance. The proposed amendment was certainly politically motivated and sui generis. President Grant personally pushed for the amendment in reaction to Reconstruction-era parochial nonsense in the South. President Grant and the proposed amendments' many Northern sponsors sent salvos into intransigent states, aimed at children's minds. I wish it had worked.

According to historians, the agony of civil war remained the base chord of the national ethos throughout Grant's presidency. For his part, President Grant tried to humanize those de-humanized in the decades or centuries before he rose to prominence -- hyphenated Americans, of which Black America was a focal point, immigrants, and Jews became targets for political benefit. Facing the hornets nests in the South and in Congress, President Grant and AG Ackerman pursued a civil rights agenda, if only politically (i.e., symbolically). He also sought to quell the successes of the Klan and similar proto-terrorist groups. The difficulty of these tasks are well stated in James William Hurst's /Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth-Century United States/. Taking Hurst's word as canon, the Grant presidency is arguably typified by the desire to enable and support activity or policy that improved one's freedom -- personal freedoms of movement, gainful employment, social well being, to name a few. The backlash of this so-called movement in favor of novel freedoms was ultimately successful; Jim Crow persisted, for example.

However, Reconstruction-era order was tenuously held, and parochial society crept toward steam mobilization and the blossoming of technological modernity in cities. old America was moving westward and European immigrants

Reconstruction Era Occasioned Communities to Resist Federal Influence, and Vice Versa

A confluence of exogenous pressures and deep seated insecurities during Reconstruction prompted Southerners and rural communities to foment resistance against normative, broad federal powers.

The newly independent empire of the United States in its explosive,

expansionist phase was organized by law built around what Willard

Hurst called "the release of energy principle." In this section of

the course we consider that regime and its effects.

Readings

Access materials on the [Course Readings] page.

Assigned

From the Notebooks of Judge Thomas Rodney of the Mississippi Territory

Suggested

Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Wisconsin Press 1956)

Notes and Materials

Projects

| | | | |

<

< | AAAaaa | | |

-- JohnOMeara - 02 Nov 2016 |

|

|