|

MichaelHiltonSecondPaper 4 - 13 Jan 2012 - Main.IanSullivan

|

|

<

< |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondPaper" |

|---|

| >

> |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondPaper2010" |

|---|

| | | It is strongly recommended that you include your outline in the body of your essay by using the outline as section titles. The headings below are there to remind you how section and subsection titles are formatted. |

|

|

MichaelHiltonSecondPaper 3 - 15 May 2010 - Main.WenweiLai

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondPaper" |

|---|

It is strongly recommended that you include your outline in the body of your essay by using the outline as section titles. The headings below are there to remind you how section and subsection titles are formatted. | | | Conservation Easements Overview | |

<

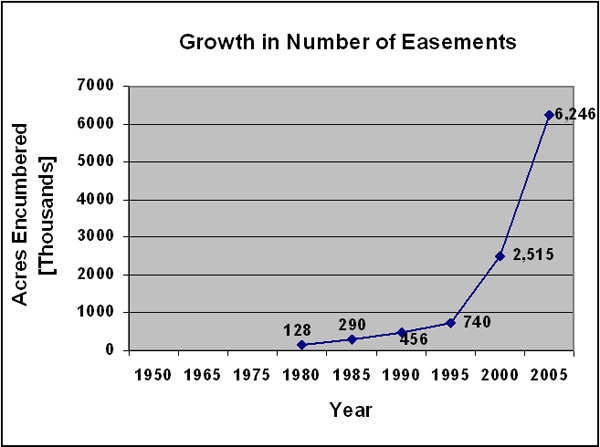

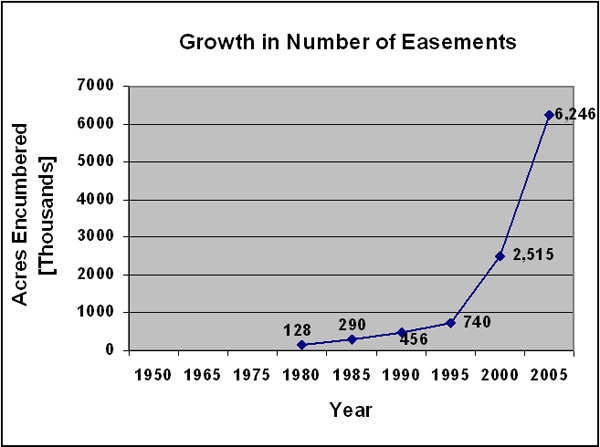

< | Conservation easements are a form of covenant which place restrictions on the use of land, and the ability to enforce this restriction is typically given to a third party such as the local government or a charitable trust. Additionally, this covenant runs with the land, and is enforceable against any owner who comes into possession. Most states today have passed legislations specifically authorizing the creation and continuation of this type of covenant. Conservation easements have only recently started gaining in popularity, growing from 2,514,566 acres affected in 2000 to 6,245,969 in 2005, an increase of 148% in a five year period. Conservation easements essentially allow a land owner to create a covenant, restricting their own options for the use of land as well as the options to which their heirs and successors possess. Conservation easements act as a bar to commercial development and subdivision, thereby ensuring the landowner’s peace of mind by giving him the knowledge his land will remain unchanged by the hands of developers, even long after his death. Furthermore, there are a variety of different tax breaks given to owners who donate conservation easements to local governments or charitable land trusts, so long as these easements fall under a rather wide range of purposes. Ostensibly, these tax breaks are given to reflect the creation of some public benefit. Whatever the benefit of conservation easements may be, I believe that there is ample evidence to show that the existence of this particular brand of covenant is in conflict with traditionally held notions of property ownership as well as established property doctrine. | >

> | Conservation easements are a form of covenant which place restrictions on the use of land, and the ability to enforce this restriction is typically given to a third party such as the local government or a charitable trust. Additionally, this covenant runs with the land, and is enforceable against any owner who comes into possession. Most states today have passed legislations specifically authorizing the creation and continuation of this type of covenant. Conservation easements have only recently started gaining in popularity, growing from 2,514,566 acres affected in 2000 to 6,245,969 in 2005, an increase of 148% in a five year period. | | | | |

<

< | Problems with Conservation Easements | >

> | Necessity for land use control | | | | |

<

< | Restraint on Alienation | >

> | The emergence of private ownership was a response to new cost-benefit possibilities. In other words, private ownership was created to internalize the externalities. However, total private ownership without any control would lead to new externalities: owner A can exclude owner B from using his own land, but he has no right to limit the ways in which B uses B’s land. Therefore, B might choose to ignore the possible negative effects on A’s land and use his own land in a way that is beneficial to himself but inefficient overall, because the harm it brings to A’s land is larger than the benefit to B’s land. A might choose to revenge and do the same thing, but it will only worsen the whole situation. The best option now is for the two parties to negotiate and reach an agreement regulating the uses of the two pieces of land. Thus, we have various means for land use control, such as easements and covenants. Conservation easements are just part of the broader scheme. | | | | |

<

< | Property law has long operated under the logic that there should be few restraints on alienation of property held in fee simple. However, the main point of conservation easements is to implement restrictions on the different uses of the land, and this has the effect of limiting who an individual can sell their land to. Because conservation easements forbid subdivisions and development of the land, the inheriting owner is left with few options. They may either continue to own the property and pay taxes on it, or sell it for a reduced price to another, who will be similarly restricted. American courts have been very hesitant to recognize restrictions attached to the alienability of inherited land, holding that such a testamentary device resembles too closely the traditional English fee tail which restricted the right of ownership to a piece of land to a particular class. This principle can be seen in the case of Johnson v. Whiton, in which the court refuses to recognize the provisions of a will which restrict who may come to own the land in question. | >

> | Prohibition of restraint on alienation | | | | |

<

< | RAP | >

> | On the other hand, property law has long operated under the logic that there should be few restraints on alienation of property held in fee simple. American courts have been very hesitant to recognize restrictions attached to the alienability of inherited land, holding that such a testamentary device resembles too closely the traditional English fee tail which restricted the right of ownership to a piece of land to a particular class. The principle can be seen in the case of Johnson v. White, in which the court refuses to recognize the provisions of a will which restrict who may come to own the land in question. The common law’s dislike for restraints on free alienation is embodied in the Rule against Perpetuities. The Rule against Perpetuities is designed to protect against dead hand control of land alienation for longer than one generation. In other words, an owner can put a restraint on his children’s ability to transfer the land, but not his grandchildren’s. | | | | |

<

< | Another piece of property law which seems to conflict with the ability of a property owner to set terms and conditions regarding the use of land which are to remain in effect perpetually is the common law Rule against Perpetuities. While not all states have or still enforce their Rule against Perpetuities, a majority of states still do, which suggests that the majority logic still supports the basic idea behind the rule. The Rule against Perpetuities is designed to protect against dead hand control of land for longer than one generation. In other words, an owner can use his will to determine the uses to which his land is put by his children, but cannot dictate the use to which it is put by his grandchildren. Furthermore, it has been recognized in the case Eyerman v. Mercantile Trust Co. (a case in which the court refused to uphold provisions of the intestate’s will) that dead hand control of land by a former owner within the immediately following generation will not be recognized if it operates to cause a waste of resources directly affecting important interests of other members of that society. It is possible that not only the inheritors of a conservation easement will be faced with wasted resources (in not being able to develop their land), but their neighbors may also experience a decrease in land value due to their proximity to land where development is restricted. | >

> | The conflict and reconciliation of the two concepts | | | | |

<

< | Tax Benefits | >

> | Prohibition of restraints on alienation seems to be inconsistent with the basic assumption of private land use control: the parties would presumably negotiate and reach a deal in a reasonable way. Actually, some commentators argue that the traditional prohibition of restraints on alienation should be abandoned and freedom of contract should be honored. To put it differently, it is not courts’ job to decide whether a restraint imposed by a landowner is reasonable or not. For other scholars, the prohibition is still worth keeping, but it must be used more prudently now than in the thirteenth century. In my opinion, the two concepts may not necessarily contradict with each other, since the rationale behind the two concepts is the same: efficient use of land. Reasonable people generally would strike a deal in an efficient way, so we should encourage freedom of contract in principle. However, people act irrationally once in a while, so prohibition of restraint on alienation such as Rule against Perpetuities is still necessary. Conservation easements should also be looked at in this light. | | | | |

<

< | A final concern regarding conservation easements is their recent and startling explosion in popularity.  Conservation easements only began growing in popularity once they became a tax-deductible interest following amendments to the Internal Revenue Code in 1976. Since it is possible for current owners to gain substantial tax deductions for donating conservation easements to local governments or approved charitable trusts, there is the possibility that many owners will act only in accordance with their own interests, not taking into consideration the effect a perpetual covenant will have on future generations who will come to own the land. Additionally, due to the exponential nature of conservation easement creation there is a substantial risk that the oversight mechanisms in place have been overwhelmed to the point where donors have the opportunity to overvalue their property without running a substantial risk of being caught. This situation creates the likely scenario that land owners can gain more individual benefit in the form of tax reductions than there is public benefit created from the preservation of the land, creating a significant public waste. While conservation easements could potentially be employed to the benefit of the general public, there would need to be more thorough evaluation of owners’ claims before the tax benefit is granted to make sure the preservation of the land will really result in public gain. As things stand at the moment conservation easements are granted for fairways on private golf courses and Nantucket cottages belonging to the wealthy, not the type of conservation likely to result in utility for the general public. Conservation easements only began growing in popularity once they became a tax-deductible interest following amendments to the Internal Revenue Code in 1976. Since it is possible for current owners to gain substantial tax deductions for donating conservation easements to local governments or approved charitable trusts, there is the possibility that many owners will act only in accordance with their own interests, not taking into consideration the effect a perpetual covenant will have on future generations who will come to own the land. Additionally, due to the exponential nature of conservation easement creation there is a substantial risk that the oversight mechanisms in place have been overwhelmed to the point where donors have the opportunity to overvalue their property without running a substantial risk of being caught. This situation creates the likely scenario that land owners can gain more individual benefit in the form of tax reductions than there is public benefit created from the preservation of the land, creating a significant public waste. While conservation easements could potentially be employed to the benefit of the general public, there would need to be more thorough evaluation of owners’ claims before the tax benefit is granted to make sure the preservation of the land will really result in public gain. As things stand at the moment conservation easements are granted for fairways on private golf courses and Nantucket cottages belonging to the wealthy, not the type of conservation likely to result in utility for the general public. | >

> | The special problem of conservation easements | | | | |

<

< | Conclusion | >

> | As one type of private land use control, conservation easements can be prima facie justified. However, the presence of governmental action complicates things. Sometimes such an action is necessary. In the basic example of private land use control, there are only two parties so it may not be hard for them to reach a deal; the negotiation cost is low. However, sometimes there are just too many people involved so it may not be efficient for them to reach a deal; the transaction cost is too high. For example, when there is one victim of a toxicant-emitting factory, a court might issue an injunction and let the parties decide how much the factory should pay to buy the injunction. On the other hand, if there are a thousand victims, the court might render monetary damages instead, because it is too hard for a thousand people to reach a consensus. | | | | |

<

< | Conservation easements, due to their perpetual nature, restraints on alienation, and questionable public utility, need to be examined closely and redefined to fit traditional norms of property law. | >

> | Nonetheless, such a remedy is inevitable subject to the doubt as to the court’s capacity to decide the amount of monetary damages. This problem is especially apparent in the creation of conservation easements. For instance, a conservation easement may be created to preserve a historical site. For such an easement to be efficient, the gain of conserving the site must be greater than the cost of giving up the mall and the tax benefits combined. Judging from the skyrocketing of the numbers of conservation easements, it is hard not to be suspicious that the tax benefits are just too high. | | | | |

<

< | Michael: | >

> | The problem with any kind of governmental intervention has always been like this: due to procedural restraints and political influences, the government can hardly do things in the most efficient way. Governmental intervention is still necessary, but it is necessary only on condition of a private system failure. Therefore, conservation easements are not inherently unjustifiable, but the use must be more limited than it is today. | | | | |

<

< | The following is my preliminary idea about the revision. It is not coherent enough to be an essay, but I think I should post it now since I have already been late for a while. I will keep revising it.

Property law has long operated under the logic that there should be few restraints on alienation of property held in fee simple. American courts have been very hesitant to recognize restrictions attached to the alienability of inherited land, holding that such a testamentary device resembles too closely the traditional English fee tail which restricted the right of ownership to a piece of land to a particular class. The principle can be seen in the case of Johnson v. White, in which the court refuses to recognize the provisions of a will which restrict who may come to own the land in question. The common law’s dislike for restraints on free alienation is embodied in the Rule against Perpetuities. The Rule against Perpetuities is designed to protect against dead hand control of land alienation for longer than one generation. In other words, an owner can put a restraint on his children’s ability to transfer the land, but not his grandchildren’s.

On the other hand, property law has various schemes to regulate land uses other than alienation: the law of nuisances, servitudes, zoning, and eminent domain. Conservation easements, though created only lately, are part of the land use controls recognized under property law.

The emergence of private property was a response to new cost-benefit possibilities. For the American Indians of the Labrador Peninsula, before the fur trade became established, hunting was carried out for personal needs such as food and clothing. The risk of externality (overhunting) was not high. However, after the fur trade came into existence, the risk of overhunting became very real: since everyone had the unlimited right to hunt in the forests, no one would refrain from doing it. Thus, the institution of private owner ship was created. Now that each person had his own land, the landowner would make the best use of his land rather than overhunting it. He was able to achieve this because now he had the right to exclude others from hunting in his land. In other words, when the externalities increased due to a changed environment, private ownership of property was created to internalize the externalities.

However, private ownership without any control would lead to new externalities: owner A can exclude owner B from using his own land, but he has no right to limit the ways in which B uses B’s land. Therefore, B might choose to ignore the possible negative effects on A’s land and use his own land in a way that is beneficial to himself but inefficient overall, because the harm it brings to A’s land is larger than the benefit to B’s land. A might choose to revenge and do the same thing, but it will only worsen the whole situation. The best option now is for the two parties to negotiate and reach an agreement regulating the uses of the two pieces of land.

In this light, the creation of conservative easement is understandable: before any regulation, a landowner has an unlimited right to use the land. He may very well demolish the historical building on the land and build a new shopping center because this is more beneficial to him economically. However, the public as a whole will suffer a loss in the demolition, which might be greater than the benefits the shopping mall will bring to the owner. Therefore, the public, whose representative is the government, should reach an agreement with the owner.

The next problem is: is the idea of land use control consistent with property law’s general dislike for restraints on free alienation? In fact, the prohibition on restraints on alienation can be justified on the same basis as land use control is justified: it is the most efficient way. If the system allows too many bundles of rights to be modified in idiosyncratic ways, both speed and certainty of exchange will be diminished. The basic idea is that well-functioning markets for land require standardized bundles of rights to work efficiently. (Some commentators doubt the efficiency of prohibition on restraints on alienation and argue for total freedom of contract. But the starting point is still to find the most efficient way to make use of land.)

Therefore, land use control and prohibition on restraints on alienation are not incompatible ideas. Are conservation easements a deviation from ordinary land use control, and thus inconsistent with the idea of efficient land use? Going back to our example: now the government has to reach an agreement with the landowner to prevent him from demolishing the historical sites. If all the actors involved were private parties, they would presumably negotiate reasonably and reach the most efficient arrangement between them. However, the intervention of the government complicates things: in what way can the government distinguish the most efficient arrangement between the landowner and the community? The gain of conserving the historical site must be greater than the cost of giving up the mall and the tax benefits combined. Judging from the skyrocketing of the numbers of conservation easements, it is hard not to be suspicious that the tax benefits are just too high.

It is exactly the problem with government intervention: due to procedural restraints and political influences, the government can hardly do things in the most efficient way. Government intervention is still necessary, but it is necessary only on condition of a private system failure. In our example, it is probably better for the community itself to negotiate with the landowner and reach an agreement with the terms acceptable to both sides. However, when the influenced community is too large, the transaction cost to reach consensus within the community may be too high. Government intervention is only necessary under such circumstances. (Zoning is based on the same idea: the government is needed for a general development scheme of a large area.) Therefore, conservation easements can be kept, but the use must be more limited than it is today. | | | |

|

|

MichaelHiltonSecondPaper 2 - 29 Apr 2010 - Main.WenweiLai

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondPaper" |

|---|

It is strongly recommended that you include your outline in the body of your essay by using the outline as section titles. The headings below are there to remind you how section and subsection titles are formatted. | | | Conservation easements, due to their perpetual nature, restraints on alienation, and questionable public utility, need to be examined closely and redefined to fit traditional norms of property law. | |

>

> | Michael:

The following is my preliminary idea about the revision. It is not coherent enough to be an essay, but I think I should post it now since I have already been late for a while. I will keep revising it.

Property law has long operated under the logic that there should be few restraints on alienation of property held in fee simple. American courts have been very hesitant to recognize restrictions attached to the alienability of inherited land, holding that such a testamentary device resembles too closely the traditional English fee tail which restricted the right of ownership to a piece of land to a particular class. The principle can be seen in the case of Johnson v. White, in which the court refuses to recognize the provisions of a will which restrict who may come to own the land in question. The common law’s dislike for restraints on free alienation is embodied in the Rule against Perpetuities. The Rule against Perpetuities is designed to protect against dead hand control of land alienation for longer than one generation. In other words, an owner can put a restraint on his children’s ability to transfer the land, but not his grandchildren’s.

On the other hand, property law has various schemes to regulate land uses other than alienation: the law of nuisances, servitudes, zoning, and eminent domain. Conservation easements, though created only lately, are part of the land use controls recognized under property law.

The emergence of private property was a response to new cost-benefit possibilities. For the American Indians of the Labrador Peninsula, before the fur trade became established, hunting was carried out for personal needs such as food and clothing. The risk of externality (overhunting) was not high. However, after the fur trade came into existence, the risk of overhunting became very real: since everyone had the unlimited right to hunt in the forests, no one would refrain from doing it. Thus, the institution of private owner ship was created. Now that each person had his own land, the landowner would make the best use of his land rather than overhunting it. He was able to achieve this because now he had the right to exclude others from hunting in his land. In other words, when the externalities increased due to a changed environment, private ownership of property was created to internalize the externalities.

However, private ownership without any control would lead to new externalities: owner A can exclude owner B from using his own land, but he has no right to limit the ways in which B uses B’s land. Therefore, B might choose to ignore the possible negative effects on A’s land and use his own land in a way that is beneficial to himself but inefficient overall, because the harm it brings to A’s land is larger than the benefit to B’s land. A might choose to revenge and do the same thing, but it will only worsen the whole situation. The best option now is for the two parties to negotiate and reach an agreement regulating the uses of the two pieces of land.

In this light, the creation of conservative easement is understandable: before any regulation, a landowner has an unlimited right to use the land. He may very well demolish the historical building on the land and build a new shopping center because this is more beneficial to him economically. However, the public as a whole will suffer a loss in the demolition, which might be greater than the benefits the shopping mall will bring to the owner. Therefore, the public, whose representative is the government, should reach an agreement with the owner.

The next problem is: is the idea of land use control consistent with property law’s general dislike for restraints on free alienation? In fact, the prohibition on restraints on alienation can be justified on the same basis as land use control is justified: it is the most efficient way. If the system allows too many bundles of rights to be modified in idiosyncratic ways, both speed and certainty of exchange will be diminished. The basic idea is that well-functioning markets for land require standardized bundles of rights to work efficiently. (Some commentators doubt the efficiency of prohibition on restraints on alienation and argue for total freedom of contract. But the starting point is still to find the most efficient way to make use of land.)

Therefore, land use control and prohibition on restraints on alienation are not incompatible ideas. Are conservation easements a deviation from ordinary land use control, and thus inconsistent with the idea of efficient land use? Going back to our example: now the government has to reach an agreement with the landowner to prevent him from demolishing the historical sites. If all the actors involved were private parties, they would presumably negotiate reasonably and reach the most efficient arrangement between them. However, the intervention of the government complicates things: in what way can the government distinguish the most efficient arrangement between the landowner and the community? The gain of conserving the historical site must be greater than the cost of giving up the mall and the tax benefits combined. Judging from the skyrocketing of the numbers of conservation easements, it is hard not to be suspicious that the tax benefits are just too high.

It is exactly the problem with government intervention: due to procedural restraints and political influences, the government can hardly do things in the most efficient way. Government intervention is still necessary, but it is necessary only on condition of a private system failure. In our example, it is probably better for the community itself to negotiate with the landowner and reach an agreement with the terms acceptable to both sides. However, when the influenced community is too large, the transaction cost to reach consensus within the community may be too high. Government intervention is only necessary under such circumstances. (Zoning is based on the same idea: the government is needed for a general development scheme of a large area.) Therefore, conservation easements can be kept, but the use must be more limited than it is today.

| | |

You are entitled to restrict access to your paper if you want to. But we all derive immense benefit from reading one another's work, and I hope you won't feel the need unless the subject matter is personal and its disclosure would be harmful or undesirable. |

|

|

MichaelHiltonSecondPaper 1 - 17 Apr 2010 - Main.MichaelHilton

|

|

>

> |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondPaper" |

|---|

It is strongly recommended that you include your outline in the body of your essay by using the outline as section titles. The headings below are there to remind you how section and subsection titles are formatted.

Waisted Space: Conservation Easements

-- By MichaelHilton - 17 Apr 2010

Conservation Easements Overview

Conservation easements are a form of covenant which place restrictions on the use of land, and the ability to enforce this restriction is typically given to a third party such as the local government or a charitable trust. Additionally, this covenant runs with the land, and is enforceable against any owner who comes into possession. Most states today have passed legislations specifically authorizing the creation and continuation of this type of covenant. Conservation easements have only recently started gaining in popularity, growing from 2,514,566 acres affected in 2000 to 6,245,969 in 2005, an increase of 148% in a five year period. Conservation easements essentially allow a land owner to create a covenant, restricting their own options for the use of land as well as the options to which their heirs and successors possess. Conservation easements act as a bar to commercial development and subdivision, thereby ensuring the landowner’s peace of mind by giving him the knowledge his land will remain unchanged by the hands of developers, even long after his death. Furthermore, there are a variety of different tax breaks given to owners who donate conservation easements to local governments or charitable land trusts, so long as these easements fall under a rather wide range of purposes. Ostensibly, these tax breaks are given to reflect the creation of some public benefit. Whatever the benefit of conservation easements may be, I believe that there is ample evidence to show that the existence of this particular brand of covenant is in conflict with traditionally held notions of property ownership as well as established property doctrine.

Problems with Conservation Easements

Restraint on Alienation

Property law has long operated under the logic that there should be few restraints on alienation of property held in fee simple. However, the main point of conservation easements is to implement restrictions on the different uses of the land, and this has the effect of limiting who an individual can sell their land to. Because conservation easements forbid subdivisions and development of the land, the inheriting owner is left with few options. They may either continue to own the property and pay taxes on it, or sell it for a reduced price to another, who will be similarly restricted. American courts have been very hesitant to recognize restrictions attached to the alienability of inherited land, holding that such a testamentary device resembles too closely the traditional English fee tail which restricted the right of ownership to a piece of land to a particular class. This principle can be seen in the case of Johnson v. Whiton, in which the court refuses to recognize the provisions of a will which restrict who may come to own the land in question.

RAP

Another piece of property law which seems to conflict with the ability of a property owner to set terms and conditions regarding the use of land which are to remain in effect perpetually is the common law Rule against Perpetuities. While not all states have or still enforce their Rule against Perpetuities, a majority of states still do, which suggests that the majority logic still supports the basic idea behind the rule. The Rule against Perpetuities is designed to protect against dead hand control of land for longer than one generation. In other words, an owner can use his will to determine the uses to which his land is put by his children, but cannot dictate the use to which it is put by his grandchildren. Furthermore, it has been recognized in the case Eyerman v. Mercantile Trust Co. (a case in which the court refused to uphold provisions of the intestate’s will) that dead hand control of land by a former owner within the immediately following generation will not be recognized if it operates to cause a waste of resources directly affecting important interests of other members of that society. It is possible that not only the inheritors of a conservation easement will be faced with wasted resources (in not being able to develop their land), but their neighbors may also experience a decrease in land value due to their proximity to land where development is restricted.

Tax Benefits

A final concern regarding conservation easements is their recent and startling explosion in popularity.  Conservation easements only began growing in popularity once they became a tax-deductible interest following amendments to the Internal Revenue Code in 1976. Since it is possible for current owners to gain substantial tax deductions for donating conservation easements to local governments or approved charitable trusts, there is the possibility that many owners will act only in accordance with their own interests, not taking into consideration the effect a perpetual covenant will have on future generations who will come to own the land. Additionally, due to the exponential nature of conservation easement creation there is a substantial risk that the oversight mechanisms in place have been overwhelmed to the point where donors have the opportunity to overvalue their property without running a substantial risk of being caught. This situation creates the likely scenario that land owners can gain more individual benefit in the form of tax reductions than there is public benefit created from the preservation of the land, creating a significant public waste. While conservation easements could potentially be employed to the benefit of the general public, there would need to be more thorough evaluation of owners’ claims before the tax benefit is granted to make sure the preservation of the land will really result in public gain. As things stand at the moment conservation easements are granted for fairways on private golf courses and Nantucket cottages belonging to the wealthy, not the type of conservation likely to result in utility for the general public. Conservation easements only began growing in popularity once they became a tax-deductible interest following amendments to the Internal Revenue Code in 1976. Since it is possible for current owners to gain substantial tax deductions for donating conservation easements to local governments or approved charitable trusts, there is the possibility that many owners will act only in accordance with their own interests, not taking into consideration the effect a perpetual covenant will have on future generations who will come to own the land. Additionally, due to the exponential nature of conservation easement creation there is a substantial risk that the oversight mechanisms in place have been overwhelmed to the point where donors have the opportunity to overvalue their property without running a substantial risk of being caught. This situation creates the likely scenario that land owners can gain more individual benefit in the form of tax reductions than there is public benefit created from the preservation of the land, creating a significant public waste. While conservation easements could potentially be employed to the benefit of the general public, there would need to be more thorough evaluation of owners’ claims before the tax benefit is granted to make sure the preservation of the land will really result in public gain. As things stand at the moment conservation easements are granted for fairways on private golf courses and Nantucket cottages belonging to the wealthy, not the type of conservation likely to result in utility for the general public.

Conclusion

Conservation easements, due to their perpetual nature, restraints on alienation, and questionable public utility, need to be examined closely and redefined to fit traditional norms of property law.

You are entitled to restrict access to your paper if you want to. But we all derive immense benefit from reading one another's work, and I hope you won't feel the need unless the subject matter is personal and its disclosure would be harmful or undesirable.

To restrict access to your paper simply delete the "#" on the next line:

# * Set ALLOWTOPICVIEW = TWikiAdminGroup, MichaelHilton

Note: TWiki has strict formatting rules. Make sure you preserve the three spaces, asterisk, and extra space at the beginning of that line. If you wish to give access to any other users simply add them to the comma separated list |

|

|