|

ThomasVanceSecondEssay 2 - 29 May 2022 - Main.EbenMoglen

|

| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondEssay" |

|---|

| | | Perhaps trust in the political process explains why those on the far right (or far left) of the Court stick with one method of framing despite different consequences for challenged legislation. Conservative justices put great faith in the political process to recognize unenumerated rights that plaintiff seeks (right to gay marriage, right to privacy, parental rights) while expressing doubt about the legislature’s ability to regulate property without effecting a taking. On the other hand, liberal justices are less trusting of the political process to protect seemingly personal rights while more trusting of and more willing to give discretion to legislatures in regulating private property (outside of permanent physical occupation cases). | |

>

> |

I think the basis of this draft is a set of accurate observations. The question for editorially is whether the interpretation is convincing.

A lifetime reading Bruce Ackerman's box-infused writing has convinced me that the product of every pair of false dichotomies is a four-box diagram. In order to write one's way through almost any case, no matter the subject matter or the form of law involved, it seems to me, there will be choices that can accurately be classified as "narrow" or "broad" In what we call "partisanship," commentary divides legal and political positions into "liberal" and "conservtive," labels that are then applied also to people. This, in turn, results from either "broad" or "narrow" applications of these labels.

Does the use of this analytical framework explain either how decisions are made or how they should be made, to take up Felix Cohen's two cardinal inquiries? If the number of decisions is limited to two, perhaps. If we ask how liberty interests under the "due process clauses" and property interests under the takings clause are defined, in more than one case each, I'm not sure that either "degree of breadth" or "degree of liberalism" will suffice to account for some votes, let alone all of them.

So the most important question in the revision of this draft might be, "what do we want our explanations of Supreme Court decisions to help us learn?" Not "the artificial reason of the law," as Edward Coke put it, perhaps. But surely more than "who is a liberal," which—at least so far as my direct experience of the Court eztends—is just not that powerful a conclusion. If we drop that particular dichotomy altogether for a moment what else might we stand to learn?

| | |

You are entitled to restrict access to your paper if you want to. But we all derive immense benefit from reading one another's work, and I hope you won't feel the need unless the subject matter is personal and its disclosure would be harmful or undesirable.

To restrict access to your paper simply delete the "#" character on the next two lines: |

|

|

ThomasVanceSecondEssay 1 - 26 Apr 2022 - Main.ThomasVance

|

|

>

> |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondEssay" |

|---|

Framing Methods Under the 5th Amendment

-- By ThomasVance - 26 Apr 2022

Introduction

This essay will explore how near-identical, ideological framing in substantive due process and takings cases yield different results.

Unenumerated Rights

Framing Methods

In substantive due process cases, a petitioner usually argues that some federal or state legislation interferes with a fundamental right. In Michael H. v. Gerald D. (U.S. 1989), plaintiff challenged a California law that created a rebuttable presumption that a child born to a married woman living with her husband is to be a child of the marriage. Michael sought custody of Victoria, a daughter he created with Carole while Carole was married to Gerald.

Since the law was challenged on substantive due process grounds, the Court began its analysis by identifying the fundamental right that Michael sought to have recognized. Conservative justices defined the right narrowly; Scalia’s plurality opinion characterized Michael’s right as the right of a child’s natural father to assert parental rights over a child born into a woman’s existing marriage with another man. Alternatively, liberal justices defined the right more broadly; Brennan’s dissenting opinion characterized Michael’s right as the right of an unwed father with a biological link and substantive relationship with his child to assert parental rights over his child. The characterization of the right is important since the Court’s analysis then turns to reviewing the right’s history, tradition, and (usually, but not in the Michael H. plurality) change over time.

Implications

Thus, if the Court looks for a narrowly-defined right, they are less likely to find instances where the Court recognized it as a fundamental right. The Court would subject the challenged legislation to rational basis review and likely find it constitutional. The opposite is true for broadly-defined rights: broad definition means the Court is more likely to find such a right in history or an analogous, recognized right. If the Court finds that the challenged legislation infringes on a fundamental right, the Court subjects the legislation to heightened scrutiny and is less likely to find such legislation constitutional.

Implicit Takings

Framing methods

The first step of Takings analysis is similar in cases where the challenged legislation neither establishes a permanent physical occupation on the landowner’s property nor regulates a nuisance. A petitioner argues that some state or municipal law constitutes a taking, entitling them to just compensation. In Penn Central Transportation Company v. City of New York (U.S. 1978), the owners of Grand Central Terminal challenged a New York City law that both designated Grand Central an urban landmark and prevented the owners from building atop of Grand Central without permission from a city commission. Penn Central argued that the statute was a taking of their air rights, entitling them to just compensation.

Like Michael H., the Court began by identifying the unit of property that it would consider in its Takings analysis. Then, the Court determined the diminution in value of the identified unit of property. Under the diminution in value test, a near total diminution in value looks like a taking.

Again, liberal and conservative justices differed on the analytical unit. The Brennan majority looked at the loss in value of the parcel as a whole following the restriction on air rights, while the Rehnquist dissent looked at the loss in value of the air rights following the restriction on air rights.

Implications

Generally, a narrow characterization of the unit of property (focusing on the burdened interest only) almost always results in a total diminution of value. Under the aforementioned test, that constitutes a taking which is unconstitutional without just compensation. A broad characterization of the unit of property (focusing on the parcel as a whole) likely will not result in a total diminution of value. The parcel as a whole likely has great value despite a government restriction on an interest in the property, so the regulation would not constitute a taking and is constitutional without just compensation.

Why the Difference

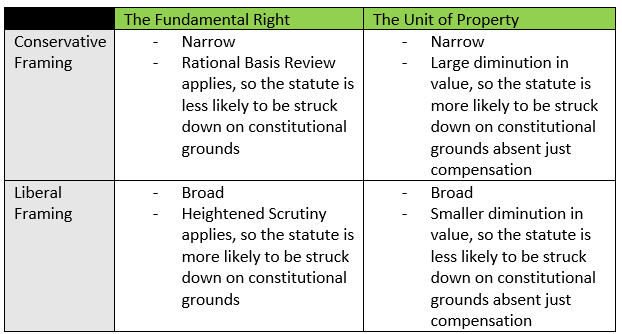

The below table helps visualize how ideological framing methods hold different fates for challenged legislation:

Table

Possible Explanations

Narrow framing makes a statute less likely to be struck down in the due process context, but more likely to be struck down (absent just compensation) in the property context. Alternatively, broad framing makes a statute more likely to be struck down in the due process context, but less likely to be struck down in the property context. Why are conservative justices more willing to intervene in the context of property rights and interests compared to the unenumerated context? Why are liberal justices less willing to intervene in the context of property rights, but more willing when it comes to substantive due process cases?

Common con-law theories seem insufficient to explain this activity. For example, a pro-legislature theory of judicial restraint could only explain narrow framing in the due process context and broad framing in the property context. Likewise, a pro-judicial activism theory could only explain the broad framing in the due process context and narrow framing in the property context.

Perhaps trust in the political process explains why those on the far right (or far left) of the Court stick with one method of framing despite different consequences for challenged legislation. Conservative justices put great faith in the political process to recognize unenumerated rights that plaintiff seeks (right to gay marriage, right to privacy, parental rights) while expressing doubt about the legislature’s ability to regulate property without effecting a taking. On the other hand, liberal justices are less trusting of the political process to protect seemingly personal rights while more trusting of and more willing to give discretion to legislatures in regulating private property (outside of permanent physical occupation cases).

You are entitled to restrict access to your paper if you want to. But we all derive immense benefit from reading one another's work, and I hope you won't feel the need unless the subject matter is personal and its disclosure would be harmful or undesirable.

To restrict access to your paper simply delete the "#" character on the next two lines:

Note: TWiki has strict formatting rules for preference declarations. Make sure you preserve the three spaces, asterisk, and extra space at the beginning of these lines. If you wish to give access to any other users simply add them to the comma separated ALLOWTOPICVIEW list.

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="lcschart.png" attr="h" comment="" date="1651013124" name="lcschart.png" path="lcschart.png" size="23801" stream="lcschart.png" user="Main.ThomasVance" version="1" |

|---|

| META FILEATTACHMENT | attachment="lcschart2.png" attr="" comment="" date="1651014702" name="lcschart2.png" path="lcschart2.png" size="23976" stream="lcschart2.png" user="Main.ThomasVance" version="1" |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

This site is powered by the TWiki collaboration platform.

All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

All material marked as authored by Eben Moglen is available under the license terms CC-BY-SA version 4.

|

|