| |

| META TOPICPARENT | name="SecondEssay" |

|---|

|

|

<

< | Framing Methods Under the 5th Amendment |

>

> | Drop the Dichotomies, Peep the Practice |

| | -- By ThomasVance - 26 Apr 2022

Introduction |

|

<

< | This essay will explore how near-identical, ideological framing in substantive due process and takings cases yield different results. |

>

> | First-year law students become all too familiar with categorizing justices and opinions as liberal or conservative. We engage in arbitrary line-drawing to help make sense of cases. This is most apparent in the substantive due process and takings clause cases. The terms liberal and conservative provide quick and dirty explanations for how and why Justices frame a sought-after unenumerated right or a unit of property. However, they are unsatisfying explanations for why justices do what they do. This essay will explore why we must and should ditch partisan explanations in favor of analyzing a jurist’s legal practice. |

| | |

|

<

< | Unenumerated Rights |

>

> | Liberal, Conservative, and Framing Unenumerated Rights |

| | |

|

<

< | Framing Methods |

>

> | Whether a justice is considered “liberal” or “conservative” cannot completely explain their approach to identifying a contested unenumerated right. |

| | |

|

<

< | In substantive due process cases, a petitioner usually argues that some federal or state legislation interferes with a fundamental right. In Michael H. v. Gerald D. (U.S. 1989), plaintiff challenged a California law that created a rebuttable presumption that a child born to a married woman living with her husband is to be a child of the marriage. Michael sought custody of Victoria, a daughter he created with Carole while Carole was married to Gerald. |

>

> | For example, in Michael H. (1989), plaintiff challenged a California law that created a rebuttable presumption that a child born to a married woman living with her husband is to be a child of the marriage. Michael sought custody of Victoria, a daughter he created with Carole while Carole was married to Gerald. |

| | |

|

<

< | Since the law was challenged on substantive due process grounds, the Court began its analysis by identifying the fundamental right that Michael sought to have recognized. Conservative justices defined the right narrowly; Scalia’s plurality opinion characterized Michael’s right as the right of a child’s natural father to assert parental rights over a child born into a woman’s existing marriage with another man. Alternatively, liberal justices defined the right more broadly; Brennan’s dissenting opinion characterized Michael’s right as the right of an unwed father with a biological link and substantive relationship with his child to assert parental rights over his child. The characterization of the right is important since the Court’s analysis then turns to reviewing the right’s history, tradition, and (usually, but not in the Michael H. plurality) change over time. |

>

> | The Court began its analysis by identifying the fundamental right that Michael sought to have recognized. Scalia’s plurality opinion is an example of how a conservative justice might define the right: the right of a child’s natural father to assert parental rights over a child born into a woman’s existing marriage with another man. Brennan’s dissenting opinion is an example of how a liberal justice might define the right: the right of an unwed father with a biological link and a substantive relationship with his child to assert parental rights over his child. Much turns on the initial identification as the Court’s next step is to investigate the existence of the right by looking to history, tradition, and (usually) change over time. If the right is not rooted in history or if the right is not analogous to a recognized right, the Court is less likely to find the challenged legislation unconstitutional. |

| | |

|

<

< | Implications |

>

> | The partisan labels – liberal and conservative – do not capture everything though. How would one classify O’Connor’s decision? O’Connor voted with Scalia but advocated for an identification of the right that Brennan likely would not disagree with. Is O’Connor’s framing liberal, conservative, or something else? |

| | |

|

<

< | Thus, if the Court looks for a narrowly-defined right, they are less likely to find instances where the Court recognized it as a fundamental right. The Court would subject the challenged legislation to rational basis review and likely find it constitutional. The opposite is true for broadly-defined rights: broad definition means the Court is more likely to find such a right in history or an analogous, recognized right. If the Court finds that the challenged legislation infringes on a fundamental right, the Court subjects the legislation to heightened scrutiny and is less likely to find such legislation constitutional. |

| | |

|

<

< | Implicit Takings |

>

> | Liberal, Conservative, and Framing Units of Property |

| | |

|

<

< | Framing methods |

>

> | Similarly, partisan labels provide convenient, but incomplete explanations for competing definitions of a unit of property in Takings cases. |

| | |

|

<

< | The first step of Takings analysis is similar in cases where the challenged legislation neither establishes a permanent physical occupation on the landowner’s property nor regulates a nuisance. A petitioner argues that some state or municipal law constitutes a taking, entitling them to just compensation. In Penn Central Transportation Company v. City of New York (U.S. 1978), the owners of Grand Central Terminal challenged a New York City law that both designated Grand Central an urban landmark and prevented the owners from building atop of Grand Central without permission from a city commission. Penn Central argued that the statute was a taking of their air rights, entitling them to just compensation. |

>

> | For example, in Penn Central (U.S. 1978), the owners of Grand Central Terminal challenged a New York City law that designated Grand Central as an urban landmark and prevented the owners from building atop of it without permission from a city commission. Penn Central argued that the statute was a taking of their air rights, entitling them to just compensation. |

| | |

|

<

< | Like Michael H., the Court began by identifying the unit of property that it would consider in its Takings analysis. Then, the Court determined the diminution in value of the identified unit of property. Under the diminution in value test, a near total diminution in value looks like a taking. |

>

> | The Court began by identifying the unit of property that it would consider in its Takings analysis. Then, the Court determined the diminution in value of the identified unit of property. Under the diminution in value test, a near total diminution in value looks like a taking. |

| | |

|

<

< | Again, liberal and conservative justices differed on the analytical unit. The Brennan majority looked at the loss in value of the parcel as a whole following the restriction on air rights, while the Rehnquist dissent looked at the loss in value of the air rights following the restriction on air rights. |

>

> | Again, liberal and conservative justices differed on the analytical unit. The Brennan (liberal) majority looked at the loss in value of the parcel as a whole following the restriction on air rights, while the Rehnquist (conservative) dissent looked at the loss in value of the air rights following the restriction on air rights. Takings cases turn on the specified unit of property. A “conservative” characterization of the unit of property almost always results in a total diminution of value. A “liberal” characterization of the unit of property likely will not result in a total diminution of value because the parcel as a whole likely has great value despite a government restriction on an interest in the property. |

| | |

|

<

< | Implications |

>

> | What, though, is ideologically liberal about a broad definition of the unit of property? What is conservative about a narrow definition of the unit of property? |

| | |

|

<

< | Generally, a narrow characterization of the unit of property (focusing on the burdened interest only) almost always results in a total diminution of value. Under the aforementioned test, that constitutes a taking which is unconstitutional without just compensation. A broad characterization of the unit of property (focusing on the parcel as a whole) likely will not result in a total diminution of value. The parcel as a whole likely has great value despite a government restriction on an interest in the property, so the regulation would not constitute a taking and is constitutional without just compensation. |

| | |

|

<

< | Why the Difference |

>

> | What Happens When You Drop The Dichotomy? |

| | |

|

<

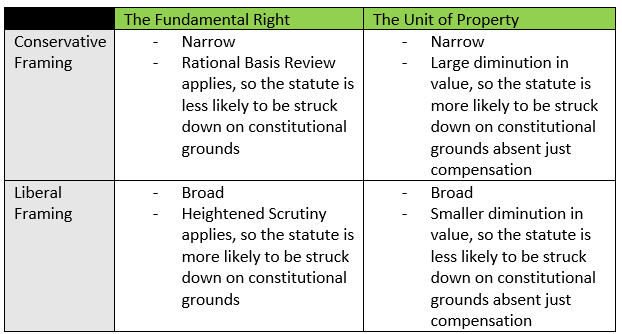

< | The below table helps visualize how ideological framing methods hold different fates for challenged legislation: |

>

> | Both the questions concerning framing units of property and regarding O’Connor’s framing of an unenumerated right expose the insufficient explanatory power of partisan labels. The labels distract from a nuanced understanding of the Court’s justices. Without the partisan labels, we are forced to discern something deeper from these cases: a peek into a justice’s practice. |

| | |

|

<

< | Table |

>

> | A law practice may be a lawyer’s license and their network, but how they balance competing legal and policy concerns as well as visions of the future is very important to their practice. This balance informs the work they do, the outcomes they seek, and the people they associate themselves with. While jurists may not be practicing lawyers, their opinions reveal pieces that undergird their practice. |

| | |

|

<

< |  |

>

> | Take O’Connor’s concurrence in Michael H. Her vote indicates that she does not think the California law infringed on one of Michael H’s fundamental rights. Her opinion rejects Scalia’s narrow framing of the right and advocates for a more general one. Combined, O’Connor’s decision (vote + opinion) cannot be neatly categorized. Instead, her decision reveals a cautionary stance toward creating an unenumerated right, and a desire to fairly (fair to the person challenging the legislation) characterize the right that plaintiff seeks recognition of. |

| | |

|

<

< | Possible Explanations |

>

> | In O’Connor’s practice, it appears that she is interested in making balanced decisions. She wants to adhere to the original and precedential text while considering the needs of plaintiffs. The word “centrist” could not capture this balance as it lacks the same nuance that liberal and conservative lack. This ability to see a case and make a decision that considers both sides of a dispute also reflects a practice that could easily identify the strongest arguments for each party and a practice that welcomes alternative and contrarian viewpoints. |

| | |

|

<

< | Narrow framing makes a statute less likely to be struck down in the due process context, but more likely to be struck down (absent just compensation) in the property context. Alternatively, broad framing makes a statute more likely to be struck down in the due process context, but less likely to be struck down in the property context. Why are conservative justices more willing to intervene in the context of property rights and interests compared to the unenumerated context? Why are liberal justices less willing to intervene in the context of property rights, but more willing when it comes to substantive due process cases? |

>

> | Conclusion |

| | |

|

<

< | Common con-law theories seem insufficient to explain this activity. For example, a pro-legislature theory of judicial restraint could only explain narrow framing in the due process context and broad framing in the property context. Likewise, a pro-judicial activism theory could only explain the broad framing in the due process context and narrow framing in the property context.

Perhaps trust in the political process explains why those on the far right (or far left) of the Court stick with one method of framing despite different consequences for challenged legislation. Conservative justices put great faith in the political process to recognize unenumerated rights that plaintiff seeks (right to gay marriage, right to privacy, parental rights) while expressing doubt about the legislature’s ability to regulate property without effecting a taking. On the other hand, liberal justices are less trusting of the political process to protect seemingly personal rights while more trusting of and more willing to give discretion to legislatures in regulating private property (outside of permanent physical occupation cases). |

>

> | Close adherence to partisan explanations of legal decisions may capture some things, but it cannot capture everything. Instead, this essay has shown that the incompleteness of partisan explanations requires dropping the dichotomies and taking a closer look into a jurist’s legal practice. |

| |

|