|

McCastle? v. Rollins Environmental Services, Inc.

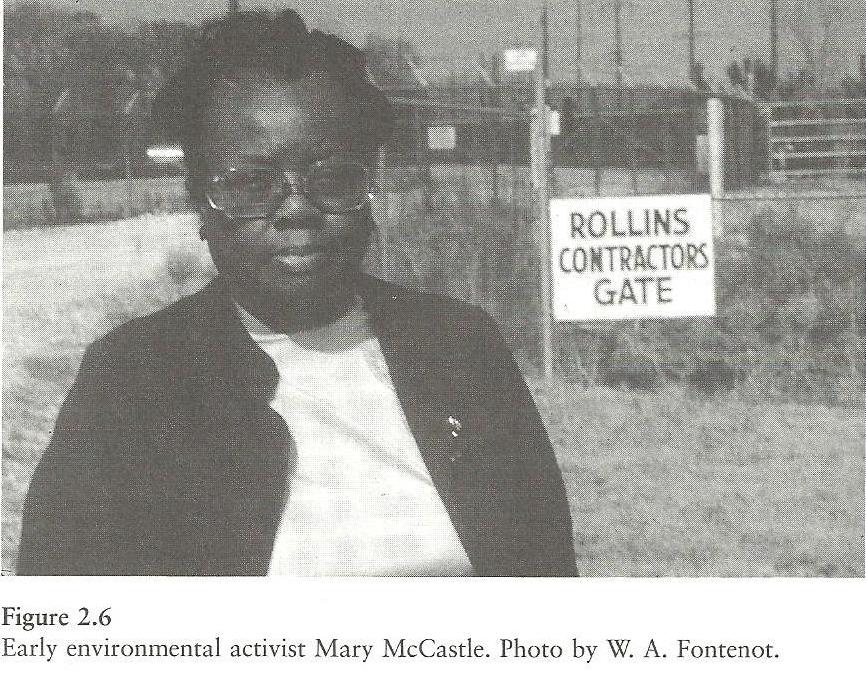

Please see the Wikipedia article here-- JenniferAnderson - May 7, 2013McCastle? v. Rollins Environmental Services, Inc.McCastle? v. Rollins is a case that was filed on behalf of the residents of Alsen (a small community located in East Baton Rouge Parish), Louisiana against Rollins Environmental Services, Inc., and (a toxic waste cleaning company). Although the decision in this case allowed the plaintiffs within this community to be certified as a class, and allowed them to be viewed as a unit when filing their lawsuit, and thereby reversing the decision that had been made at the trial and appellate level, the case was not reheard in the lower courts. Instead, Rollins Environmental Services, Inc. settled with the plaintiffs outside of court. Although this case is primarily cited for what a group of people need to do in order to obtain class certification, it is also often cited as one of the pivotal moments in the environmental justice grass roots movement that has been occurring within communities of color. The people involved in the suit look at the way in which their community was disproportionately impacted by toxic waste polluters in light of their race and class, in comparison to communities that are composed of people who are racially and economically privileged and advocated for more considerate treatment by state regulators and operators of waste disposal plants. Through looking at the development of the McCastle? v. Rollins lawsuit, one can see the way in which class, race, legal claims, community activism, public health and environmentalism can be viewed and used in conjunction with one another to protect the rights of people living within a given community.ContentsBackgroundAlsen is a small community located in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Before the civil war, it was known as the Mount Pleasant plantation; after the civil war, slaves that were freed from the Mount Pleasant plantation and from neighboring plantations came and settled in the area. The People who live there have a very close connection to the land. (1) It is just one community that has been the hosts of corporations that pollute their communities. This area known as cancer alley is often cited as one of the most toxic areas in the country with residents claiming a host of ailments and health conditions. Cancer alley is the 107 mile stretch along the Mississippi river that runs between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. This area has over 150 environmental hazards and waste dumps that are located there. More than 60 percent of the facilities that release chemicals are located within communities that are populated by people of color (African Americans, Latinos, Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans). Louisiana has policies and characteristics that are favorable to businesses. They are located off the Gulf of Mexico and are afloat in oil. (2) In the 1960s, tax exemptions and business friendly policies that were made under Governor John McKeithen? , attracted many businesses are attracted to this area of Louisiana. (Burke 112) A lot of companies move their operations to that state to take advantage of business friendly standards and policies that take a relaxed view of environmental standards and health issues. As a consequence, the land in Louisiana is some of the most industrially injured land in the United States. (Burke 111) More times than not, hazardous facilities were placed in areas that were composed primarily of people of color. Due to historical racism, people of color did not have a lot of political and social power and were unable to challenge the ways in which their communities were being changed.[5] Often time local government and big business would exploit this group of peoples and continue racism that had occurred during colonial times. (Burke 111) Rollins Environmental Services, Incorporated was a company that had the fourth largest landfill in the country in 1986. At that time, it represented 11.3 percent of the permitted hazardous-waste capacity in the United States. (3)The Facility opened in 1969 and had been operating to clean toxins since then.Beginning of the Social MovementThe group involved in the McCastle? case is located in Alsen. Around the time of the initial filing of the lawsuit in 1980, there were 1104 residents. African American composed 98.9 of those residents. More than 77 percent of the people who lived there owned their own homes even though it had started out as a rural community that was primarily composed of African Americans.[6] William Fontenot, an environmental advocate, met with McCastle? and a group of community members at her house in her living room to talk about the pollution that was creating the poisonous fumes. Many of the community members were not trusting of white people who came into their presence; they usually just came around to get votes. (4) Willie Fontenot was the one who linked the community group to the lawyers that would be able to help them push their lawsuit through the court system. This group claimed that Rollins Environmental Services was land farming sludge that was being produced by Exxon Corporation. This pollution was causing a host of health issues within the community. (Add the ailments that it was causing).Mary McCastle? , a 75 year old grandmother, and a number of other local residents were determined to protect the health rights of other members within their communities. As a result, they formed the Coalition for Community Action. McCastle? and other local residents began to record the impact that these facilities had on the community members and the physical landscape of their locals. As Mary McCastle? stated: "We had no warning Rollins was coming in here. When they did come in we didn't know what they were dumping. We did know that it was making us sick. People used to have nice gardens and fruit trees. They lived off their gardens and only had to buy meat. Some of us raised hogs and chickens. But not after Rollins came in. Our gardens and animals were dying out. Some days the odors from the plant would be nearly unbearable. We didn't know what was causing it. We later found out that Rollins was burning hazardous waste."[7] These claims were not limited to Mary McCastle? 's testimony. In addition, residents in this Louisiana community claimed the pollution from Rollins also produced health issues such as cancer, asthma, and heart disease. This organization worked to have Rollins Environmental Services clean up some of the waste that they had disposed of for Exxon Mobil by reporting the practices of Rollins Environmental Services to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality.[9] Even though residents were invited to watch Rollins Environmental Services clean up the waste that they had disposed of inappropriately, they didn't see much of the clean up getting done. Consequently, the group of residents followed up and filed a law suit on behalf of community members who had been adversely impacted.[10]}Law SuitA group of residents that lived in Alsen, an East Baton Rouge Parish, and Louisiana filed a law suit against a chemical land farming operation, Rollins Environmental Services. There were approximately 4,000 residents that were part of the claim. They lived adjacent or in close proximity of the Rollins center and claimed that the land farming “had polluted the air and caused them injury.” (McCastle? v. Rollins 615) They were represented by Steve Irving and Dennis R. Whalen. There were two things that the claimants were trying to achieve. One was class certification and the other was to obtain damages and an injunction for the Rollins facility to stop their operation which was polluting the community. In terms of class certification at the trial court level, the group of plaintiffs was denied class certification because the court perceived their injuries to be too divergent, not easy to identify, and the plaintiffs wanted large damages. At the Appeal level, the court confirmed the findings of the trial court. The appeals court didn't think that dealing with the claims of the members of the community together would create judicial economy. The Supreme Court of Louisiana reversed the findings of the trial and appeals court and said that it would be impractical to have all of the separate plaintiffs file separate briefs since they are similar enough.[11] In order to determine whether it was appropriate to deem the people involved in this case should be part of a larger class, the court went through a process of analysis. Common Character Analysis ( As laid out in La.C.C.P. articles 591(1) and 592 and exemplified in Guste v. General Motors Corp. 370 So. 2d 477, Williams v. State, 350 So.2d 131 (La.1977), and Stevens v. Board of Trustees, 309 So.2d 144 (La.1975)). [12] The three Requirements are: 1. A class so numerous that joinder is impracticable, and 2. The joinder as parties to the suit one or more persons who are (a) Members of the class, and (b) So situated as to provide adequate representation for absent members of the class, and 3. A "common character" among the rights of the representatives of the class and the absent members of the class. The appellate acknowledged that the class in the Alsen case had the first two characters that are necessary to be accepted as a class but not the “common character” factor. (Rollins v. McCastle? 616). Through doing an analysis of the Common Character, determined that the group of people who went to trial for this case fulfilled all of the qualities that would be necessary for a group of people to be considered a class (617). • Effecting Substantive law (618) • Class actions deal with issues that may not otherwise be litigated • They allow the court to see what the ramifications of their decision will be on the interested plaintiffs and the liability on the defendant. • The interests of absentees would be taken into account • Judicial efficiency (619) • Necessary to achieve economies of time, effort, and expense • The Supreme Court determined that the lower courts had mischaracterized the relationship of the relationship o the various people to one another. They claimed the same harms, the same causes of the harm, and lived within the general vicinity of one another. • Individual fairness (621) • This involves the uniformity of the decision among the members of the class. • Each of the people in the class is asserting a similar, if not identical claim. Through walking through these claims, the court determined that it was practical for litigation to proceed as a class. The certification was approved and the plaintiff's case was sent to lower court to be reevaluated.[13] In terms of the injunction and the damages, the case was remanded back to the lower court to determine what actions should be taken against the facility and what types of damages the members of the community would receive. (621 McCastle? v. Rollins) Under the authority of 28 USCS § 1441, the court was able to assert the injunction so that the facility would stop emitting toxic fumes into the atmosphere.Aftermath of the CaseAfter the court decision that said that the group could be certified as a class, the case was settled outside of court in 1987. Each of the plaintiffs received between $500 and $3,000 dollars. The Alsen Community did not receive the health clinic that they had hoped to receive. The Rollins Environment Services, Inc. facility that was at the center of the lawsuit is now closed. Immediately after the suit, it was not closed, but the performance of the facility did improve. (5) Also it was perceived as a problematic depositor of chemical waste. In 1989 the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, that had members from the Alsen community who had been negatively impacted by environmental and health conditions, were able to successfully prevent the expansion of the Rollins’ facilities. (6) In 1992, The Coalition for Community Action was successful in obtaining a technical assistance grant (TAG) from the federal Environmental Protection Agency to obtain cleanup in an area called the Devil's swamp which is also located in the East Baton Rouge Parish.[15] "DEVIL’S SWAMP LAKE EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH LOUISIANA". Environment Protection Agency Region 6. Retrieved April 9, 2013. The Tulane Environmental Law Clinic has worked with the North Baton Rouge Environmental Association and has helped them have many of their claims heard.[17]Social ImplicationsOne legacy of the environmental justice movement was the fight against Supplemental Fuels incorporated (SFI). Although the company tried to locate its facilities in a community where they thought that people would not fight back, they were met by opposing black and white forces. After a long court battle, the company left Louisiana. This incidence showed that when communities come together to challenge people who want to move into their communities they can be successful. (7)Court CasesMcCastle? v. Rollins Environmental Services, 514 F. Supp. 936 (1981) McCastle? v. Rollins Environmental Services, Inc., 415 So. 2d 515 (1982) McCastle? v. Rollins Environmental Services, Inc., 456 So. 2d 612 (1984)Primary SourcesAllen, Barbara L. Uneasy Alchemy: Citizens and Experts in Louisiana's Chemical Corridor Disputes Toxic Waste and Civil Rights (http://www.loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=94-P13-00003&segmentID=1) Allen, Barbara L. Uneasy Alchemy: Citizens and Experts in Louisiana's Chemical Corridor Disputes Schwab, Jim, Deeper Shades of GreenSecondary SourcesMarkowitz, Gerald and David Rosner. Deceit and Denial; The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution Hackle, Angel. Master’s Thesis: Brown University Motavalli, Jim. Toxic Targets; Polluters that Dump on Communities of Color Are Finally Being Brought to Justice Houck, Oliver A., SAVE OURSELVES: THE ENVIRONMENTAL CASE THAT CHANGED LOUISIANA

|

|